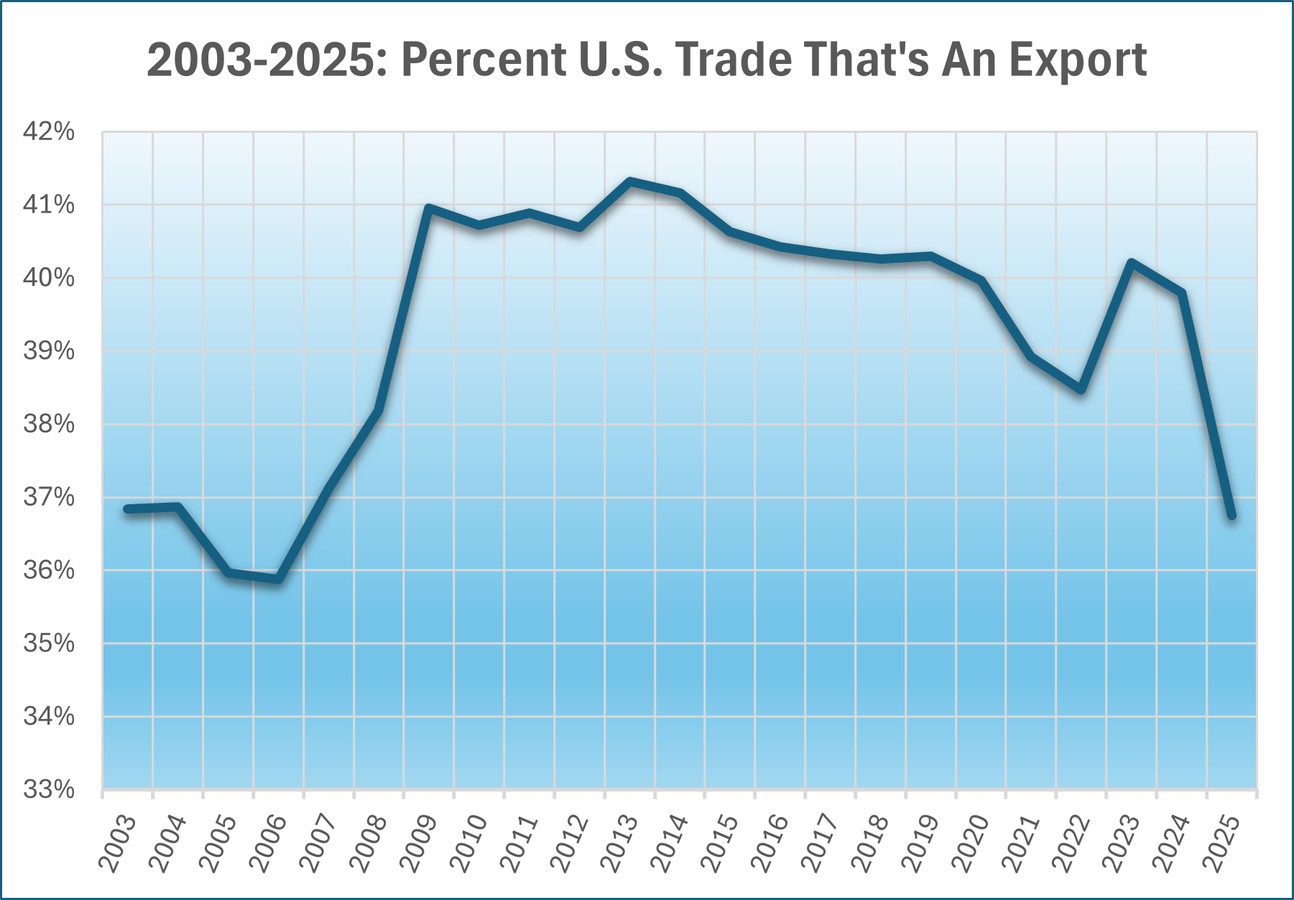

For many years, the U.S. trade deficit increased — but the percentage of U.S. trade that was an … More

Yes, U.S. trade is running at a record pace this year. Yes, that includes record exports. Yes, that includes record imports. Soon enough, we will see how much of that was stockpiling ahead of threatened tariffs from President Trump, in the 47th term of a U.S. president.

But there’s one number going in the wrong direction, and I am not talking about the trade deficit. That, too, is of course at a record pace as well through April, according to the latest U.S. Census Bureau data I analyzed.

The number I watch, and watch closely despite its seemingly slight movements, is the ratio between exports and imports. That number stood at 36.75% through April.

If U.S. exports stay at 36.75% of total U.S. trade through 2025, it will be the lowest level since … More

The last time the United States finished a year below that was the four years from 2003 through 2006.

Not before, to my knowledge, and not since.

What’s different now is that, generally speaking across the last three decades, the ratio of exports has either grown or remained steady, as the chart at the top of this post shows. Not now.

Hold on, this one might seem a little wonky but the only real concept at play here is this: The ratio of exports to imports is every bit if not more important than the difference between the two.

Let’s start with what’s so special about those four years? That was right after China entered the World Trade Organization and unleashed its manufacturing might on the United States and the world.

China is, of course, at the center of Trump’s tariff war with the world, announced April 2, quickly paused, and scheduled to resume in early July.

But almost every year after that four-year trough, as the Chinese appetite for U.S. exports increased, that percentage moved toward the historical norm of 39.95%.

That might not sound like a big difference 36.75% and 39.95% – but when U.S. annual trade is $5.33 trillion, as it was in 2024, a 1% move is equal to $53.3 billion. A move of 3.2 percentage points – in other words, to the average over the last three decades – is equal to $170.56 billion.

I can’t imagine there’s an exporter in this country who wouldn’t want at least a little of that action.

What happened in the decade after that four-year trough? U.S. exports to China from 2006 to 2016 were larger than to any other country in the world, except Mexico, which was benefitting from the North America Free Trade Agreement.

While not growing as much, exports to China were growing faster than those to Mexico. That’s because China was starting from a smaller base. U.S. exports to China increased 83.67% compared to 69.39% for Mexico – even with the more difficult logistics involved.

The growth in exports – imports from China were also rising rapidly, as was the U.S. deficit with China – showed up in the U.S. percentage of trade with China that was an export. It increased from a rather paltry 15.72% in 2006 to a slightly less paltry 20.01% in 2016.

U.S. exports to China, through April, by percentage.

While the increasing trade deficit (exports minus imports) represents the strength of American buying power, the percentage of total trade that is an export (exports divided by total trade) represents billions in additional U.S. exports of soybeans, aircraft, medical devices and more.

Since 2016, that export ratio has continued to climb.

In the nine full years since, it has topped 20% seven times, falling below for only the first two years of Trump’s first term. Thus far in 2025, the percentage is 23.81%.

That’s still well below the average with the world, of course, at just under 40%. And there’s no disputing that the high tariffs that Trump put on U.S. imports from China in his first term, tariffs generally left in place by former President Joe Biden, have had an impact on the trade relationship.

I have written about how the U.S. deficit with China, five times greater than any other deficit with the world when Trump entered office the first time, is now only 50% greater than that of Mexico. And yet, the U.S. deficit continues to climb, topping $1 trillion six of the last eight years.

I have written that China’s percentage of U.S. trade dipped to its lowest level in more than two decades. And yet, U.S. trade continues to climb, as other trade partners, Vietnam among them, have continued to grow rapidly.

I have written that China has slipped to rank third among U.S. trade partners, after ranking first, that it also fell behind Mexico as an importer into the United States. Trade with Mexico has been robust – and the U.S. deficit with Mexico has swollen as China’s has retracted.

I have written that most symbolic of Chinese imports, the cell phone, and its related parts, dipped to their lowest level in two decades. And cell phone imports have remained robust but shifted to India and Vietnam.

I have written about what the Trump administration deemed the “Dirty 15,” those countries with which the United States has its largest trade deficits. Most are both our largest export markets and our allies.

For decades, the United States government, albeit begrudgingly, seemed to believe that a focus on U.S. exports would eventually be better than a narrow focus on the trade deficit. While China lags behind most other top trade partners and top large economies in its percentage of trade that is an export, its progress has been unrivaled.

Could China have gotten to 30%? What about 40%? Could it still?

What would China look like if its economy was able to buy an additional $800 billion in exports from the United States? Could the United States produce that much? Could it grow enough soybeans? Could Boeing manufacture enough jets? Could U.S. drug makers increase their output sufficiently? Could U.S. automakers, and even foreign automakers building cars in the United States and employing “blue-collar” Americans, produce enough cars?

It would, of course, extend beyond merchandise trade. American brands would be coveted. It would extend to service trade, to hotel chains, to restaurant chains, to movies, to our universities and to increased tourism in the United States.

What a boost to the U.S. economy that would be.

That view, that a laser-sharp focus on increasing exports would be better than reducing the deficit, is no longer in vogue.

And yet, despite all that, our trade has continued to grow, our imports have continued to grow, our exports have continued to grow, albeit more slowly, our trade deficit has continued to grow – and our percentage of trade that is an export has fallen.