Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

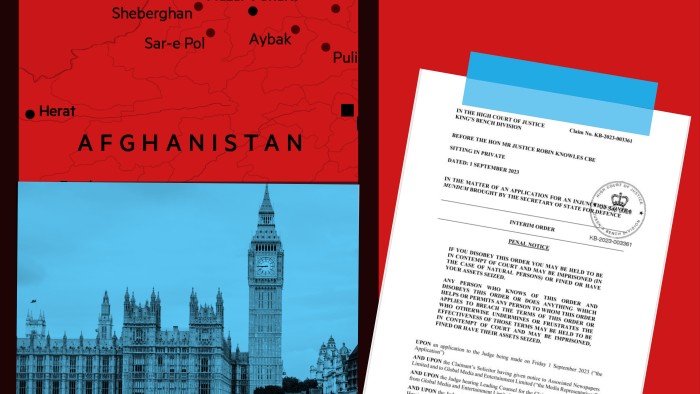

Rarely has a UK cabinet minister made such an extraordinary admission to parliament as that by defence secretary John Healey on Tuesday: a catastrophic data breach under the previous Conservative government endangering the safety of thousands of Afghans who assisted British forces in the Afghanistan conflict; a top-secret, multibillion-pound scheme to relocate them to the UK; a “super-injunction” intended to protect them, but which banned any disclosure of what was happening. It is now for parliamentary and other inquiries to evaluate what went wrong, and how governments responded. But there are serious questions about whether governments hid too long behind secrecy arguments to keep parliament, and the public, in the dark.

A central focus must be how such a vast and costly security breach could have come about. As Healey conceded, it was one of “many” data losses related to a scheme to relocate Afghans who aided the UK. Three in September 2021, involving 265 names, already led to a probe by the Information Commissioner’s Office, a fine and a shake-up of procedures. A full investigation of how a British soldier in February 2022 sent two emails accidentally including details of 19,000 Afghans who had applied for resettlement plus 6,000 family members is now essential to ensure something similar could not happen again.

Once the Conservative government learnt of the leak in August 2023 it had a clear moral obligation to protect those put at risk, including creating a new scheme for several thousand people on the list most at risk who were not eligible for the existing relocation plan.

Failure to safeguard all those in the dataset, had the Taliban government obtained it, could have left individuals who had supported British interests vulnerable to reprisals including torture or murder. It could also have destroyed local trust in UK forces in operations elsewhere, hindering their effective functioning.

A review commissioned by Healey this year from Paul Rimmer, a former deputy chief of defence intelligence, concluded it was unlikely today that appearing in the dataset would trigger Taliban retribution. The Labour government has closed its special relocation scheme to new applicants. But it seems reasonable for its Tory predecessor to have acted according to security assessments it was given at the time. Current ministers should also monitor any signs of reprisals against Afghans remaining in the country, and be ready to restart relocations if needed.

The duty to protect at-risk Afghans inevitably entailed secrecy, certainly in the initial stages. The government judged that if the existence of the leak were publicised, the Taliban was more likely to obtain the data. Its application for an injunction was granted by a High Court judge who banned even disclosure of the order’s existence. But coming reviews should examine whether the government relied too long on secrecy arguments. Mr Justice Chamberlain, who finally lifted the super-injunction on Tuesday following arguments by media groups including the Financial Times, showed in his judgments that he was acutely conscious of the restrictions on press freedom and public debate.

Another motive for ministers to prolong the secrecy may have been concerns over possible public disorder, after far-right protests last year. Yet local communities might have shown more understanding had they known the real reason for many Afghan arrivals. It would be entirely wrong for any party to seek to fan tensions over the issue. Officials at all levels, however, should now face long-overdue scrutiny over the entire sorry episode.