BBC

BBCTom Parker was working alone three miles (4.8km) off the Devon coast when his fishing boat hit a wave and lurched to one side.

“I was pulling one of the ropes and I slipped and fell,” he says. “I had this really, really bad pain in my ankle. So much so, I couldn’t get up off the floor.”

He didn’t know it at the time, but Tom, 37, had broken his fibula and badly damaged his ankle ligaments.

He somehow hauled in his fishing gear and made it to hospital to get patched up, but months after the accident his wound just wouldn’t heal properly.

It was only after he turned up at an innovative clinic on the quayside in Brixham that he was put on strong antibiotics and told he needed a second operation.

“Without that service, I would have probably ended up with my leg turning septic and I’m not too sure what would have happened after that,” he says.

Under a 10-year plan, published last month, health officials said the NHS in England needed to undergo a radical shift, away from hospitals to community care, and away from treating sickness to preventing it in the first place.

There are already small-scale examples of that approach in action across the country.

So what can we learn from the Brixham model and how can the idea of targeted, local care be extended to treat millions more NHS patients?

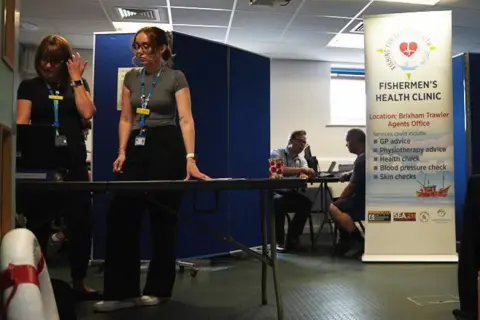

On a clear summer morning a spare room in the trawler agent’s offices in Brixham harbour is quickly being converted into a temporary health clinic.

Blue screens are dragged across to split up the space: a makeshift reception at the front and then just enough room to cram in two GPs, a pharmacist, a physiotherapist, two nurses and someone organising prostate cancer tests.

There’s a steady line of port workers coming in, from buyers in the fish market next door to crews from the trawlers in the harbour.

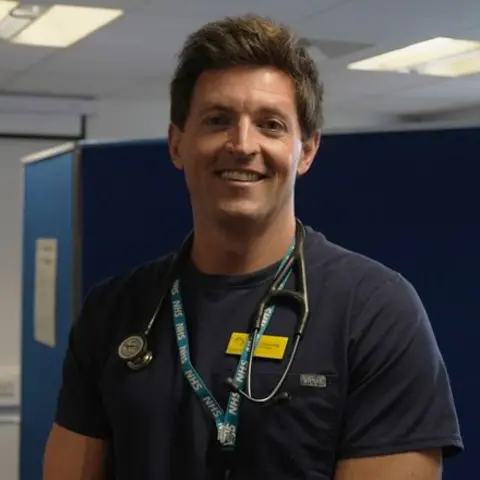

“The skippers of the boats and the whole fishing community now know exactly where to find us,” says Dr James Gunning, the local NHS GP in charge of the clinic that day.

“They’re a community that fits into health inequalities, where a population either can’t access, or struggles to access, normal NHS services.”

Clinic staff start early in the morning, walking around the docks and coaxing workers off the boats with promises of free health screenings and physio.

“Fishermen don’t have nine-to-five jobs, they don’t have lunchtime where they can just pop off their fishing boat and to the GP’s office, and so it’s really important that we take those services to them,” says Sandra Welch, chief executive of the Seafarers Hospital Society, which runs the initiative along with another charity, the Fishermen’s Mission.

A pop-up Seafit clinic operates every three months in Brixham and at similar sites at ports across the UK, including Folkestone, Peterhead and Kirkeel in Northern Ireland.

Some services have started to expand and now offer skin cancer checks, mobile dental services and access to mental health counselling.

In its 10-year plan the NHS accepts that those who live in coastal and rural areas are more likely to experience worse health outcomes and to die younger.

Seaside and coastal towns often have older populations with more complex health needs, while at the same time local NHS services can suffer from recruitment problems, leaving staffing gaps where they are needed most.

An analysis of hospital statistics by the BBC suggests NHS trusts in England treating coastal communities tend to have higher than average wait times for both emergency care and appointments booked in advance, like surgery.

The answer, according to NHS bosses and the Westminster government, is to shift as much treatment as possible out of those expensive hospitals.

Under the 10-year plan a network of 300 neighbourhood health centres will be opened across England, starting in areas with the lowest healthy life expectancy.

The sites, which should eventually be open 12 hours a day, six days a week, will be staffed by a mix of GPs, nurses, social care workers, pharmacists, mental health specialists and other medics.

The big idea, as with the Brixham fishermen’s clinic, is to better tailor health services to local communities, and offer people more checks and tests to stop them falling sick in the first place.

Much of this might feel very familiar.

Similar ambitions were set out by ministers in 2019, 2015 and even by the Blair government back in the early 2000s.

“Despite being the right aim, none of those truly delivered,” says Luisa Pettigrew, a GP and senior policy fellow at the Health Foundation think tank.

“Moving money out of hospitals and into community services is hard to do. You need the upfront investment and the results might not be visible for five or 10 years, in some cases longer.”

Healthcare unions have also questioned how the new centres will be staffed, saying doctors “must not be moved around like pieces on a chess board or made to work even harder”.

The medics working in Brixham though are convinced their local, preventative approach can benefit not just the fishing community but the wider health service.

“We’ve managed to find new diabetic patients who otherwise may have gone on to develop more serious disease,” says Dr Gunning.

“We’ve picked out others with cardiovascular disease, and those with high blood pressure. So we would certainly hope we can prevent more costly illness from developing.”

Rob Caunter, who finally retired from the fish market this year, is just finishing his radium treatment for prostate cancer.

The 66-year-old, who has a family history of the disease, was diagnosed after staff at the clinic convinced him to take a blood test.

“I was gobsmacked really because I didn’t think there was anything wrong with me,” he says.

“If I never went for the checks, I don’t think I would be here today. So it was a real godsend for them to come down to the quay.”