Ali Abbas AhmadiBBC News, Toronto

Canadian Space Agency

Canadian Space AgencyIn a shopping plaza an hour outside Toronto, flanked by a day spa and a shawarma joint, sits a two-storey building with blue tinted windows reflecting the summer sun.

It is the modest headquarters of Canadensys Aerospace, where Canada is charting its first trip to the Moon.

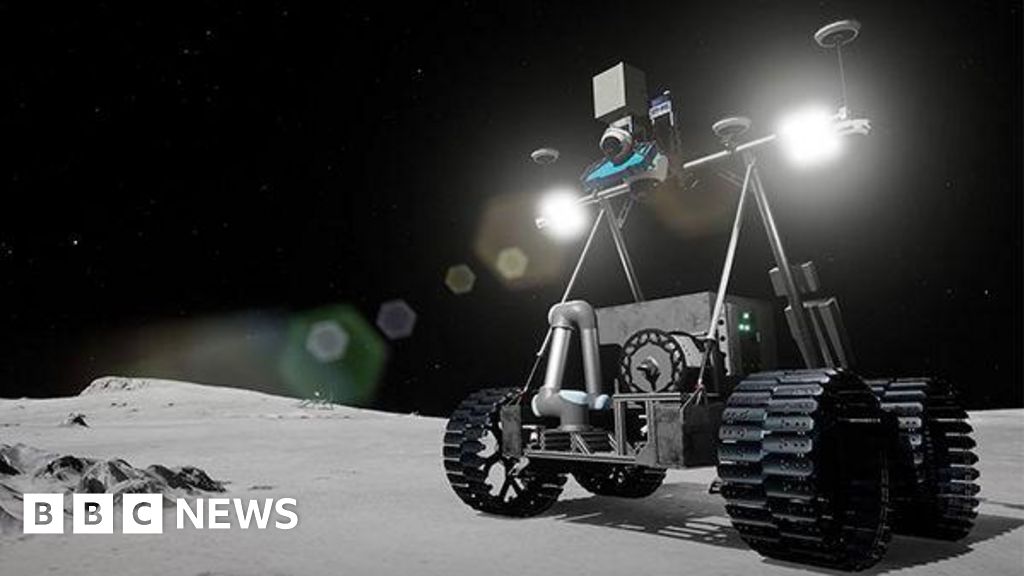

Canadensys is developing the first-ever Canadian-built rover for exploring the Earth’s only natural satellite, in what will be the first Canadian-led planetary exploration endeavour.

Models, maps and posters of outer space line the office walls, while engineers wearing anti-static coats work on unfamiliar-looking machines.

Sending this rover to the Moon is part of the company’s “broader strategy of really moving humanity off the Earth”, Dr Christian Sallaberger, Canadensys’ president and CEO, told the BBC.

Learning about the Moon – which is seen to have the potential to become a base for further space exploration – is the “logical first step”, he said.

“People get all excited about science fiction films when they come out. You know, Star Wars or Star Trek. This is the real thing.”

The Canadian vehicle is part of Nasa’s Artemis programme, which aims to establish a sustainable human presence on the Moon.

As part of that overarching goal, this rover aims to find water and measure radiation levels on the lunar surface in preparation for future manned missions, and survive multiple lunar nights (equivalent to about 14 days on Earth).

The rover will also demonstrate Canadian technology, building on Canada’s history in space.

Canada was the third country to launch a satellite, designed the Canadarm robotic arms for the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station, and is known for astronauts such as Chris Hadfield and Jeremy Hansen – the latter of whom will orbit the Moon on the Artemis II mission next year.

The 35kg rover is scheduled to be launched as part of a Nasa initiative in 2029 at the earliest. It will land on the Moon’s south polar region – one of the most inhospitable places on the lunar surface.

The vehicle does not have a name yet. The Canadian Space Agency held an online competition to select one, and is expected to announce the winner in the future.

Canadensys is currently working on several prototypes of the rover. The final vehicle, Mr Sallaberger said, would be assembled shortly before launch.

Each component is tested to ensure it can survive the Moon’s harsh conditions.

Temperature is one of the main obstacles. Lunar nights can plummet to -200C (-328F) and rise to a scorching daytime of 100C (212F).

“It’s one of the biggest engineering challenges we have because it’s not so much even surviving the cold temperature, but swinging between very cold and very hot,” he said.

Designing the wheels is another challenge, as the Moon’s surface is covered with a sticky layer of fragmented rock and dust called regolith.

“Earth dirt, if you look at it microscopically, has been weathered off. It’s more or less in a round shape; but on the Moon the lunar dirt soil is all jagged,” Mr Sallaberger said.

“It’s like Velcro dirt,” he said, noting it “just gums up mechanisms”.

The search for water on the lunar surface is especially exciting, considering the Moon was generally thought to be bone dry following the Apollo missions in the 1960s and 70s, the US human spaceflight programme led by Nasa.

That perception changed in 2008, Dr Gordon Osinski, the mission’s chief scientist, told the BBC, when researchers re-analysed some Apollo mission samples and found particles of water.

Around the same time, space crafts observing the Moon detected its presence from orbit.

It has yet to be verified on the ground and many questions remain, the professor at Western University in London, Ontario, said.

“Is it like a patch of ice the size of this table? The size of a hockey rink? Most people think, like in the Arctic, it’s probably more like grains of ice mixed in with the soil,” he said.

Water on the Moon could have huge implications for more sustainable exploration. He noted one of the heaviest things they need to transport is often water, so having a potential supply there would open doors.

Water molecules can also be broken down to obtain hydrogen, which is used in rocket fuel. Mr Osinski described a future where the Moon could become a sort of petrol station for spacecrafts.

“It gets more in the realms of sci- fi,” he said.

Canada has wanted to build a lunar surface vehicle for decades, with talk of a Canadian-made spacecraft even in the early 2000s – but it was not until 2019 that concrete plans were announced.

Canadensys was awarded the C$4.7m ($3.4m; £2.5m) contract three years later.

Founded in 2013, Canadensys has worked on a variety of aerospace projects for organisations like Nasa and the Canadian Space Agency, as well as commercial clients.

More than 20 instruments built by the company have been used in a host of missions on the Moon.

But there are challenges ahead – as even landing on the Moon is no easy feat.

In March, a spacecraft by commercial US firm Intuitive Machines toppled over onto its side during landing, ending the mission prematurely.

Three months later, Japanese company iSpace’s Resilience lost touch with Earth during its landing, and eventually failed.

“That’s the nature of the business we’re in,” Mr Sallaberger said. “Things do go wrong, and we try to do the best we can to mitigate that.”

Intuitive Machines/The Planetary Society

Intuitive Machines/The Planetary SocietySpace exploration has been a collaborative field over the years, with countries – even rivals, such as the United States and Russia – working together on the International Space Station.

But that might be changing, Mr Osinski said. As the prospect of a permanent presence on the Moon becomes more realistic, wider geopolitical questions have begun to swirl around the ownership of the satellite.

“There’s more talk around who owns the Moon and space resources,” Mr Osinski said.

In 2021, the US passed a law to protect the Apollo Moon landing site “because they had a concern that China could just go and grab the US flag, or take a piece of an Apollo lander”, he said.

But he had some encouraging words about the Artemis missions, which are “even way more international than the space station”.

The Artemis Accords, which is a set of ideals to promote sustainable and peaceful exploration of outer space, has been signed by more than 50 countries – including ones like Uruguay, Estonia and Rwanda, which are not traditionally seen as key space race nations.

Space is also becoming more accessible. Private companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin have taken an increasingly important role and are able to take anyone with the money and barely any training – like Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and pop star Katy Perry – into space for a few minutes.

But the Moon is the Holy Grail, as it opens up all sorts of possibilities.

Mr Sallaberger said that Canadensys is involved in longer-term projects, such as lunar greenhouses for food production.

Those still remain many years in the future, but the rover is a starting point.

“If you design something that can survive on the lunar surface long-term, you’re pretty bulletproof anywhere else in the solar system.”