On July 4, 2025, President Trump signed into law the 2025 budget reconciliation bill, formerly known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, that makes significant changes to Medicaid eligibility and financing. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the law will cut federal Medicaid spending by $911 billion over 10 years and will increase the number of people who are uninsured by 10 million in 2034.

One source of the law’s Medicaid cuts is a 10-year moratorium on implementation or enforcement of provisions in two rules finalized by the Biden administration that would have reduced administrative burdens to make it easier for people to enroll in and maintain Medicaid and CHIP coverage (See Box 1). In effect, the law delays or pauses implementation of many provisions in the two rules until October 2034. To ease the administrative burden on states, the implementation dates for the changes in the rules spanned a three-year period, with some provisions taking effect in 2024 or 2025 and others with implementation dates in 2026 and 2027. Some provisions are excluded from the 10-year delay, including those that have already taken effect.

Box 1: Medicaid Eligibility Rules

The Medicare Savings Program (MSP) rule , finalized in September 2023, aims to reduce barriers to enrollment of Medicare beneficiaries with low incomes in the Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs), through which Medicaid pays Medicare premiums, and in most cases, cost sharing. Among other changes, the rule requires states to automatically enroll Medicare beneficiaries with Supplemental Security Income (SSI) into the MSPs and more closely aligns the MSP application to the application for Medicare’s Part D prescription drug Low-Income Subsidy (LIS).

The second rule, the Eligibility and Enrollment (E&E) rule, was finalized in April 2024 and seeks to more broadly streamline application, enrollment, and renewal processes in Medicaid. It requires states to simplify eligibility and reduce barriers to enrollment for certain individuals, aligns renewal policies for individuals who qualify on the basis of modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) and those who qualify on the basis of being age 65 or older or having a disability (referred to as non-MAGI groups), facilitates transitions between Medicaid, separate Children’s Health Insurance Programs (CHIP) and the Basic Health Plan (BHP), and reduces barriers to children’s coverage in CHIP.

While the provisions in the final rules involve numerous technical changes to eligibility, enrollment, and renewal policies, collectively, they aim to streamline complex processes that make it difficult for individuals to enroll in Medicaid and CHIP coverage and maintain that coverage, and, therefore, would increase projected enrollment over time. The delay in implementing provisions in these final rules along with other provisions in the law, such as new work and reporting requirements and more frequent eligibility determinations for individuals enrolled in the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion, will increase administrative barriers (or red tape) to Medicaid and CHIP that are projected to result in fewer people enrolling in coverage and many people losing coverage. While some of the people who lose coverage from these changes are no longer eligible, it is expected that most of the projected enrollment declines will be among people who are eligible.

While the law prohibits the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) from implementing or enforcing provisions subject to the delay until October 1, 2034, it does not prohibit states from implementing the changes. In some cases, states have already made the changes required by the rules, either in anticipation of implementation of the new requirements or as part of other efforts to streamline or simplify processes. Whether states maintain or rollback the changes they are no longer required to keep in place will influence how much the budget reconciliation law’s delay affects Medicaid coverage and federal spending.

This issue brief describes the impact of delaying key provisions from those rules on federal Medicaid spending and coverage; and identifies which provisions across both rules are not delayed and which are. Where available, it also indicates how many states have already implemented provisions that are now delayed.

Estimated Impact on Federal Medicaid Spending and Coverage

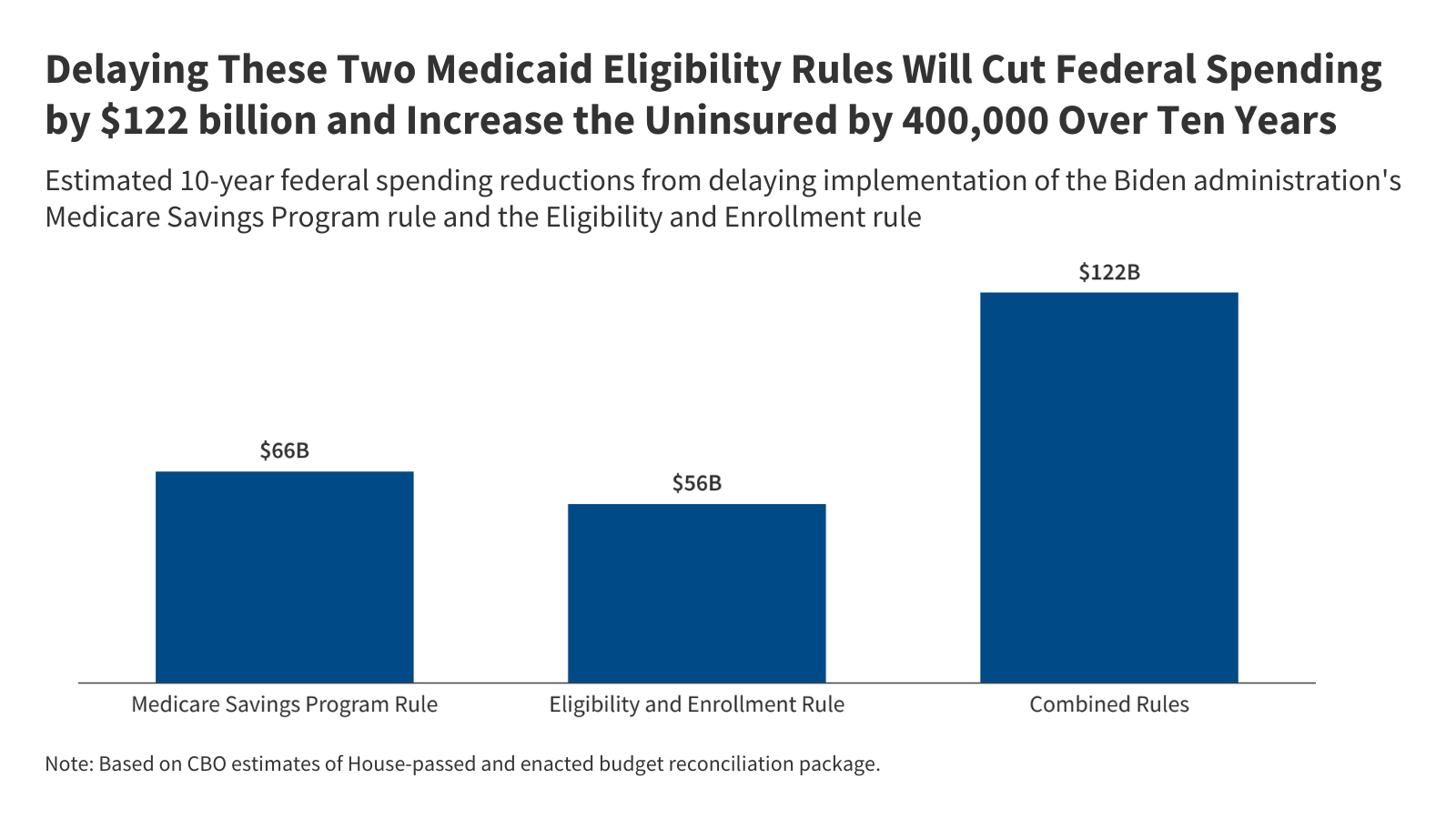

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that delaying certain provisions in the two rules will reduce federal spending by $122 billion over ten years and increase the number of people without health insurance by 400,000 in 2034. Delaying provisions is projected to save the federal government $66 billion from the MSP rule and $56 billion from the E&E rule over ten years. These combined reductions in federal spending represent about 12% of the total reductions in federal Medicaid spending from the law. CBO estimates that the delayed provisions will increase the number of people without health insurance by 400,000 in the year 2034, but the impact on the number of people enrolled in Medicaid will be higher. Some Medicare beneficiaries who are eligible for MSP and would have enrolled in Medicaid because of provisions in the MSP rule will not enroll in Medicaid. However, these individuals will retain their Medicare coverage and will not become uninsured. Although CBO did not provide a detailed analysis of the impact on Medicaid enrollment, an earlier analysis of the House-passed version of the bill showed that 1.3 million fewer “dual eligible individuals” (people who are enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare) would be enrolled in Medicaid in 2034. Because of differences in the version of the bill passed by the House and the final enacted law, the drop in the number of dual eligible individuals may be lower.

Medicare Savings Program Rule

Provisions That are not Delayed

The only provision in the MSP rule that is not delayed took effect October 1, 2024 and requires all states to automatically enroll Supplemental Security Income (SSI) recipients into the Qualified Medicare Beneficiary (QMB) Medicare Savings Program (MSP) (Table 1). SSI provides monthly payments to older adults and people with disabilities who are unable to work and have limited income and resources. The Medicare Savings Programs provide Medicaid coverage of Medicare premiums, and in most cases, cost sharing to low-income Medicare beneficiaries. The QMB program is one of the four types of Medicare Savings Programs, and pays for Part A and B premiums, deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments. Medicare beneficiaries are eligible for the QMB program if their monthly income is below the FPL ($1,304 per month for an individual and $1,763 per month for a couple in 2025) and if their assets are below the resource limit ($9,660 for individuals and $14,470 for couples in 2025).

The rule notes that because the income and resource eligibility criteria for the QMB group exceeds those for SSI, individuals who qualify for SSI will always meet the requirements for QMB eligibility. The automatic enrollment of SSI recipients into the QMB program increases enrollment among eligible people by allowing them to avoid the administrative burden of separate eligibility processes.

Provisions That are Delayed

The law delays several provisions that would facilitate MSP enrollment using the Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) data. The Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) is a program that helps Medicare beneficiaries pay for prescription drugs. To increase participation in LIS, people who enroll in an MSP are automatically enrolled in LIS, but not all people in LIS are automatically enrolled in an MSP. The Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008 requires the Social Security Administration (SSA) to send LIS applications to states and for states to treat those data (e.g., “LIS data”) as an application for the MSPs, but not all states do so.

The rule strengthens the requirement for states to treat LIS data as an application for the MSPs by establishing clear steps for states to take upon receiving the data from the SSA and prohibiting states from requiring a separate application for MSP. The rule also requires states to provide LIS applicants with information about the availability of full Medicaid benefits and the opportunity to apply for those benefits.

The law delays provisions that encourage states to use the Medicare Part D LIS definitions of financial eligibility. A barrier for states in using LIS data to initiate an application to the MSPs is that the two programs have different methods for measuring income and financial resources. For example, the MSPs include certain types of income and assets that are excluded from the LIS definition and that can be cumbersome for applicants to document. States also often use different definitions of family size when calculating income eligibility for MSP purposes than those used for LIS eligibility.

The rule encourages states to align LIS and MSP eligibility criteria by requiring states to use the LIS definition of family size (unless the state definition is more generous) and by creating incentives for states to adopt the definitions of financial eligibility used in the LIS program. States that elect to keep their methods for defining financial eligibility rather than using the LIS criteria, will be required to accept applicants’ self-reported information for any income and assets that are not included with the LIS application. States must enroll in the MSP all applicants whose self-reported financial information meets state eligibility criteria unless they have data that are incompatible with the self-reported information. When states require additional information from applicants, they will be required to take a more active role in helping applicants find the information, such as contacting financial or fiduciary institutions on behalf of applicants.

The law pauses a provision that requires Qualified Medicare Beneficiary (QMB) coverage to begin earlier for certain Medicare beneficiaries who do not qualify for free Part A premiums through their own earnings or those of a spouse, parent, or child, and must pay the Medicare Part A premium. Currently, some people who do not qualify for premium-free Part A may have to pay the premium out-of-pocket before QMB coverage begins and may be unable to qualify for QMB coverage if they are unable to afford the premium (ranging from $285 or $518 per month in 2025 depending on people’s work history). This occurs for people who did not enroll in Part A when they first became eligible for Medicare and live in states that do not have a “buy-in” agreement with the federal government. A “buy-in” agreement allows states to enroll eligible people directly into Medicare on a year-round basis and pay their monthly premiums. In states without such agreements, people may only enroll in Part A during the annual general enrollment period between January 1 and March 31. Under the rule, states will be required to start QMB coverage and payment of Part A premiums for eligible applicants after the SSA receives a conditional application for Part A, so applicants will not have to pay premiums prior to gaining coverage.

Medicaid, CHIP, and Basic Health Plan Eligibility and Enrollment Rule

Provisions That are not Delayed

The rule eliminates barriers to CHIP coverage for children, including lockout periods for nonpayment of premiums, waiting periods, and annual or lifetime limits on coverage, effective June 2025. Prior to the rule, states had the option to lock children out of coverage in separate CHIP programs for nonpayment of premiums by preventing reenrollment for a specific period. States were also allowed to impose waiting periods in separate CHIP programs that required children to be uninsured for a certain period of time, usually 90 days, before enrolling in CHIP coverage, and could impose annual and lifetime dollar limits on CHIP benefits. The rule prohibits coverage lockout periods for nonpayment of premiums, waiting periods, and any dollar limits on CHIP benefits.

The rule also seeks to improve transitions between Medicaid and separate CHIP programs to reduce gaps in coverage for children. Without coordination between Medicaid and CHIP programs, children whose family income or circumstances change and must transition from one program to another are at risk of experiencing delays in enrollment in the other program or gaps in coverage during the transition. As of June 2024, Medicaid and CHIP agencies are required to accept eligibility determinations from the other program and provide a joint eligibility notice to reduce confusion for families whose children are moving from one program to the other.

Another enrollment simplification policy in the rule that has taken effect is ending the requirement that applicants apply for other benefits as a condition of Medicaid eligibility. Under previous policy, states were required to evaluate individuals’ available income and resources for other benefits they may qualify for, such as annuities or pensions before determining eligibility for Medicaid. The rule removes the requirement for enrollees/applicants to apply for other benefits that do not impact an individual’s eligibility for Medicaid or CHIP. The rule redefines available income and resources to only include resources the individual is in immediate control of.

The rule also reduces burdens for applicants by limiting requests for documentation to verify assets. When determining Medicaid eligibility, states are required to check available data sources for income information and must apply a reasonable compatibility standard, which specifies the acceptable level of variance between an individual’s self-reported income and the income information returned from available data sources before requesting additional documentation from an individual. While these rules apply to income verification, the requirements for verifying assets were less clear. The rule clarifies that states must use available data sources to verify assets for applicants subject to an asset test, which includes most people who apply on the basis of age or disability. States must also apply a reasonable compatibility standard when verifying assets. If asset information provided by an individual is reasonably compatible with information returned through an asset verification system, the state may not request further documentation from the individual.

The rule allows states to permit applicants for medically needy coverage to prospectively deduct new types of medical expenses. People may qualify through a medically needy pathway if their income is higher than permitted under a different pathway but lower than the medically needy limit, or if they “spend down” to the medically needy limit by deducting health care expenses from their income. Previously, individuals applying through the medically needy pathway could only prospectively deduct medical expenses for institutional care. The rule allows individuals who are not in institutional settings to deduct prospective medical expenses, such as home care and prescription drugs, when applying for Medicaid coverage through the medically needy pathway.

To enhance program integrity, the rule updates requirements for how and how long states must maintain case records. Outdated regulations that do not specify what information from case records state must maintain have led to inconsistencies in recordkeeping across states and have contributed procedural payment errors captured in CMS’ annual Payment Error Rate Measure (PERM) rates because of insufficient documentation. The rule specifies that states must maintain records for all eligibility determinations in an electronic format, clarifies what information must be contained in the records, and requires that records be kept for a minimum of three years. These provisions take effect in June 2027 and were the only provisions in the rule that were not subject to the delay in implementation even though they had not yet been implemented.

Provisions Subject to the Moratorium on Implementation

The law pauses implementation of provisions that align renewal policies for individuals eligible through MAGI and non-MAGI pathways. The ACA created consistent, streamlined application and renewal policies for individuals who qualify for Medicaid based on modified adjusted gross income (“MAGI”); however, these policies were not extended to “non-MAGI” enrollees who qualify for Medicaid based on old age or disability. The rule requires states to extend the streamlined MAGI procedures to non-MAGI individuals. These include eliminating in-person interviews as part of eligibility determinations, requiring states to renew coverage no more frequently than every 12 months, requiring that non-MAGI applications and forms be accepted through the same modalities as MAGI applications and forms, and requiring states to send pre-populated renewal forms to non-MAGI enrollees whose ongoing eligibility cannot be confirmed through available data sources. As of January 2025, all states have stopped in person interviews, 47 states offer applications and forms to non-MAGI applicants in all the same modalities as forms sent to MAGI applicants, and 37 states send pre-populated renewal forms to non-MAGI enrollees.

Provisions to clarify state and enrollee requirements when changes in enrollee circumstances occur were also paused. States are required to redetermine eligibility when reported or identified changes in circumstances may affect an individual’s eligibility. If information is needed from the individual to complete a redetermination, states are required to give enrollees a minimum of 10 days to respond to these requests. Unlike individuals who lose coverage at their regularly scheduled renewal, individuals disenrolled for failure to provide additional information relating to a change in circumstance are not given a 90-day reconsideration period during which they can submit information confirming ongoing eligibility and have their coverage reinstated.

The rule updates and clarifies steps states must take in responding to changes in circumstances. It specifies that if a state identifies a change in circumstance that may affect an enrollee’s eligibility, the state must first attempt to verify the change with available data. If there is not sufficient data to verify the change, the state must contact the enrollee and request additional information and must provide the enrollee with at least 30 calendar days to respond to the request. The rule also requires states to provide a 90-day reconsideration period if an enrollee is disenrolled for failure to provide the requested information. As of January 2025, 7 of the 15 states that conduct periodic data checks to identify changes in circumstances already provide at least 30 calendar days for enrollees to respond to requests for additional information.

The law delays implementation of updates to state performance and timeliness standards for eligibility determinations at application that apply these standards to eligibility redeterminations at renewal and following changes in circumstances. Current rules require states to develop performance and timeliness standards for determining eligibility at application. States are required to complete eligibility determinations at application within 90 days for people applying on the basis of disability and 45 days for all other applicants. The rule extends the performance and timeliness standards to eligibility redeterminations at regularly scheduled renewals and following identification of changes in circumstances.

Other provisions that are delayed include more efficient data matching, required state processes to respond to returned mail, and clarification of continued benefits during renewal periods. The rule simplifies eligibility verification by allowing for verification of citizenship with a State vital statistics agency or DHS SAVE to be considered evidence of citizenship that does not require additional documentation. When a state receives returned mail with no forwarding address, the rule establishes a three-step process where the state must check reliable sources for updated address information; if updated information is unavailable, take additional steps to confirm the enrollee’s address using modalities other than mail; and if unable to contact the enrollee, move the enrollee to a fee-for-service delivery system, suspend coverage, or terminate coverage. The rule clarifies that states must provide continued enrollment and benefits to enrollees during a review if the state fails to make a timely eligibility redetermination.