Changes are coming to Medicare’s drug price negotiation program that could result in at least $5 billion in additional Medicare spending over time, if not more, and higher out-of-pocket costs for people with Medicare. Under the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program, the federal government is required to negotiate with drug companies for the price of some high-spending drugs that have been on the market for several years without competition, with the goal of lowering Medicare drug spending and helping to reduce out-of-pocket costs for people with Medicare. The law that established the negotiation program, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, excluded certain types of drugs from negotiation, including orphan drugs approved to treat a single rare disease or condition. The new tax and budget reconciliation law passed by Congressional Republicans and signed by President Trump modifies the orphan drug exclusion in ways that will lead to higher Medicare spending, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), and higher costs for beneficiaries who take these medications.

Takeaways

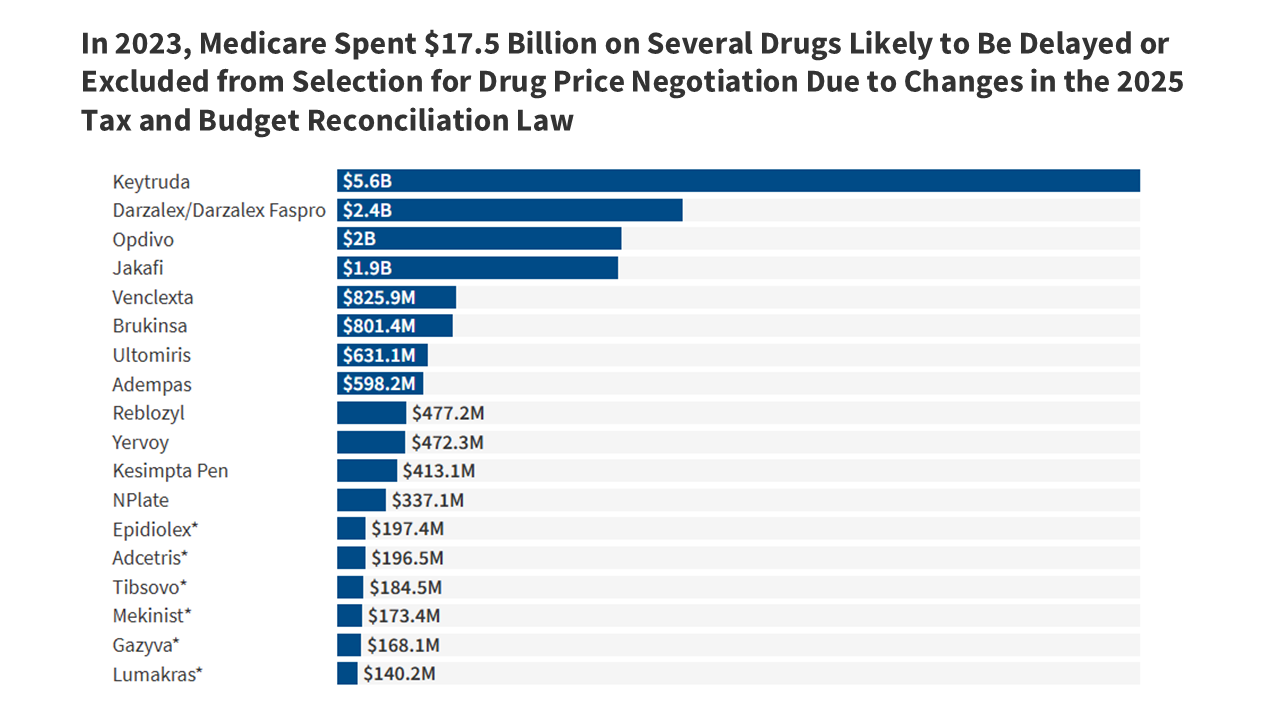

- The new tax and budget law will result in delayed eligibility or exclusion from Medicare drug price negotiation for several high-spending drugs, including a number of cancer drugs and other medications with $17.5 billion in total spending by Medicare and beneficiaries in 2023. For example, the changes in law are expected to delay selection of Keytruda and Opdivo, both on the market since 2014, by at least one year. In 2023, Medicare and beneficiaries spent $5.6 billion on Keytruda and $2.0 billion on Opdivo. Several other drugs are also likely to be delayed in their eligibility to be selected for negotiation or are now ineligible for negotiation unless they receive non-orphan approvals in the future.

- Expanding the orphan drug exclusion to allow more drugs to be delayed or excluded from Medicare drug price negotiation, as under the new tax and budget law, will mean higher out-of-pocket costs for Medicare beneficiaries who use these medications. Medicare’s negotiated drug prices can help to lower the amount beneficiaries pay, particularly in situations where they face a coinsurance requirement that is calculated based on the underlying price of the drug, such as in the case of Part B drugs and higher-cost Part D drugs. By delaying or excluding additional orphan drugs from selection for price negotiation, the tax and budget law will maintain higher prices for these drugs relative to the price Medicare would have paid if the drugs had been eligible and selected for drug price negotiation, which will translate to higher out-of-pocket liability. For example, if the government were to negotiate a 22% discount off the price of Keytruda, on par with the average 22% net price discount from the first round of Medicare drug price negotiation, that would generate annual savings on cost-sharing liability of around $3,300 for Medicare beneficiaries who use Keytruda.

- Delaying or excluding orphan drugs from Medicare drug price negotiation will cost the federal government several billion dollars over the coming decade – nearly $5 billion according to CBO, but this amount is likely to be an underestimate because it reportedly doesn’t fully account for the changes to the orphan drug provision in the new tax and budget law. This amount could also grow over time based on how the pharmaceutical industry responds in terms of changes in orphan drug research and development and the pipeline of new drugs coming to market and changing incentives around seeking additional orphan indications (as well as non-orphan indications) for orphan drugs already on the market.

What is the orphan drug exclusion and how does the new tax and budget law modify it?

Under the IRA, drugs that are designated for only one rare disease or condition with approvals under that one designation were excluded from Medicare drug price negotiation. This exclusion helped to address pharmaceutical industry concerns about the potential dampening effect on orphan drug research and development if drugs approved to treat a single rare disease were subject to Medicare price negotiation. After enactment of the IRA, efforts to expand the orphan drug exclusion were launched, based on pharmaceutical industry and rare disease advocacy group concerns about the potential impact on research and development for multi-orphan drugs. This echoes broader claims made by the industry about the impact on drug development associated with other policies to reduce drug prices, even as high drug prices create affordability and access challenges for patients. Nevertheless, lobbying efforts culminated with the inclusion of changes to the IRA’s orphan drug exclusion supported by the pharmaceutical industry in the recently enacted tax and budget law.

Changes in the tax and budget law include broadening the orphan drug exclusion to make orphan drugs that are designated for multiple rare diseases or conditions, not just a single rare disease, ineligible for Medicare drug price negotiation, and delaying the start of the 7- or 11-year waiting period for selection for drug price negotiation for orphan drugs that subsequently receive FDA approval for a non-orphan indication. Under the IRA, small-molecule drugs must be 7 years past FDA approval and biologics 11 years past FDA licensure when drugs are selected for negotiation. Under the new tax and budget law, for orphan drugs, this 7- or 11-year waiting period begins only when the drug has received approval for a non-orphan indication.

While these changes to Medicare’s drug price negotiation program might appear to be relatively minor, they will result in some very high-spending drugs becoming eligible for negotiation later than they otherwise would have been and other drugs will be excluded entirely unless they are approved for non-orphan uses in the future. Taken together, these changes have the potential to reduce savings to Medicare from the negotiation program and lead to higher beneficiary out-of-pocket costs.

The new tax and budget law could impact which high-spending drugs are selected for negotiation in the coming year

A number of drugs that were expected to be selected for Medicare drug price negotiation in the near future based on meeting the criteria for selection – including total Medicare spending of more than $200 million, lack of generic or biosimilar equivalents, and a sufficient number of years since FDA approval – are now likely to be off the table, either delayed in their eligibility to be selected for negotiation or no longer eligible. Among them are several high-spending cancer drugs, including Keytruda, Darzalex, Opdivo, and Jakafi, along with several other medications used to treat various types of cancer and other medical conditions (Table 1).

In 2023, spending by Medicare and beneficiaries on these drugs totaled $17.5 billion, an 83% increase since 2019 ($9.5 billion), based on Medicare Part B and Part D drug spending data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (Figure 1, Table 2). These estimates include Part D spending under both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage but Part B drug spending in traditional Medicare only, since Medicare Advantage spending data are unavailable. Of these medications, Keytruda alone accounts for 32% of the total, with $5.6 billion in spending in 2023, up from $2.7 billion in 2019. Of the 734 drug and biologic products included in CMS’s Medicare Part B drug spending data for 2023, Keytruda ranked number one in terms of total spending by Medicare and beneficiaries, excluding any spending by enrollees in Medicare Advantage.

The change in law is expected to delay selection of Keytruda and Opdivo for price negotiation by at least one year, with a longer delay or exclusion from negotiation applying to other medications

Changes to the orphan drug exclusion will take effect beginning with the third round of drug price negotiation in 2026, with the selection of drugs required to be announced no later than February 1, 2026, and Medicare’s negotiated prices for these drugs taking effect on January 1, 2028. The changes are likely to have an immediate impact on which drugs are selected for Medicare price negotiation in 2026 by delaying the selection of Keytruda and Opdivo, which were likely to be selected for negotiation next year based on their total spending levels and meeting other statutory criteria.

- Keytruda, manufactured by Merck, was first approved as an orphan drug to treat melanoma in September 2014 and was subsequently approved for a non-orphan indication for non-small cell lung cancer in October 2015, followed by several other approvals for additional indications, broadening its use beyond the original rare disease approval. Under the IRA, Keytruda would have been eligible to be selected for price negotiation in February 2026, since that will be more than 11 years after its initial FDA approval, and Medicare’s negotiated price would have been available in 2028 if it had been selected next year. But under the new tax and budget law, Keytruda’s eligibility to be selected for negotiation will be delayed a year to 2027, with Medicare’s negotiated price available in 2029 if it is selected for negotiation. This is because the 13-month period that Keytruda was on the market as an orphan-only drug will not count towards the 11-year waiting period following initial FDA approval that determines when biologic drugs potentially become eligible for selection.

- A similar delay likely applies to Opdivo, manufactured by Bristol Myers Squibb, which was first approved as an orphan drug to treat melanoma in December 2014 but was subsequently approved for a non-orphan indication for non-small cell lung cancer in March 2015. Opdivo’s eligibility to be selected for negotiation will be delayed a year from 2026 to 2027, assuming the drug continues to meet other criteria for selection.

A longer delay likely applies to other orphan drugs, including Yervoy, manufactured by Bristol Myers Squibb, which was first approved as an orphan drug to treat melanoma in March 2011 but was subsequently approved for non-orphan indications for kidney cancer in April 2018 and colorectal cancer in July 2018. Eligibility for Yervoy to be selected for negotiation will likely be delayed by four years, from 2026 to 2030.

Exclusion from negotiation will now apply to several other orphan drugs based on the new tax and budget law’s changes to the IRA’s orphan drug exclusion provision. For example, Jakafi (manufactured by Incyte), Venclexta (manufactured by AbbVie), and Darzalex (manufactured by Janssen Biotech) are orphan drugs with multiple orphan designations and approvals but no non-orphan approvals, which previously made them eligible to be selected for negotiation under the IRA, but they are no longer eligible under the new tax and budget law, unless they receive approval for wider uses in the future.

The high price of these drugs has contributed to their relatively high annual Medicare spending per user

Total spending by Medicare and beneficiaries on a single claim for each of these drugs in 2023 exceeded several thousand dollars – in many cases, $10,000 or more – which translated to annual total spending per user of tens of thousands of dollars. For example, spending on the blood cancer drug Jakafi under Medicare Part D was $16,700 per claim and $138,200 per user in 2023; spending on Keytruda under Medicare Part B was $12,600 per claim and $76,100 per user in 2023, and for Opdivo, Part B spending was $10,500 per claim and $69,800 per user (Figure 2). While the total number of Medicare beneficiaries using any one of these medications is relatively low compared to more commonly used drugs – around 70,000 for Keytruda in 2023 and fewer than 30,000 for the other medications (Table 2) – their high prices translate to relatively high annual spending under Medicare.

Coinsurance requirements for high-cost Part B and Part D drugs translate to high out-of-pocket costs for Medicare beneficiaries

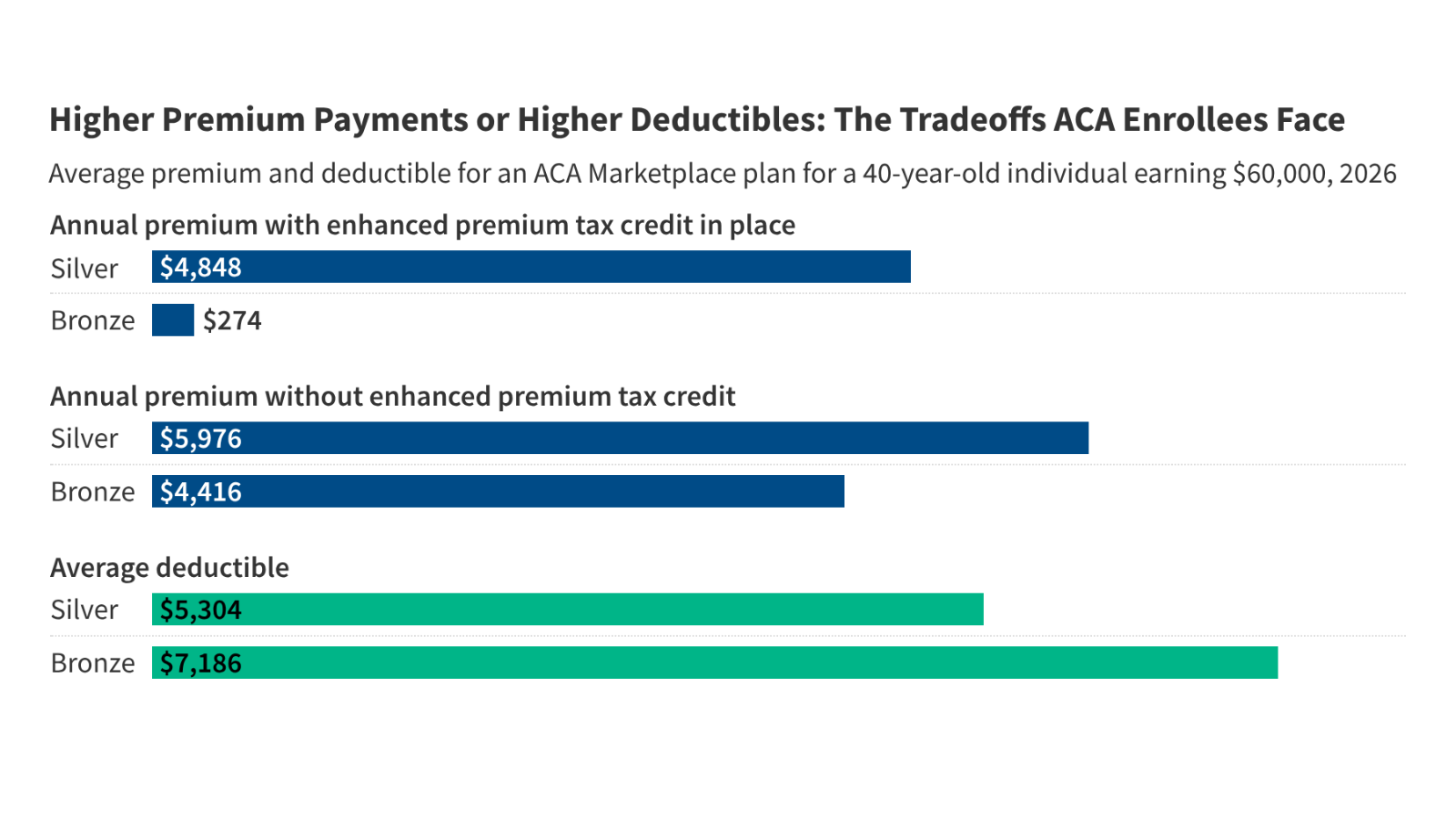

For high-priced drugs covered under Part B or Part D, beneficiary cost-sharing requirements in the form of coinsurance (a percentage of the drug’s total price) can translate to several hundred dollars, if not $1,000 or more, each time they fill a prescription or are administered the drug.

- Under Medicare Part B, which primarily covers physician-administered medications like Keytruda, Darzalex, and Opdivo, beneficiaries in traditional Medicare face a 20% coinsurance requirement. Most but not all traditional Medicare beneficiaries have some type of additional coverage to help with their Medicare cost-sharing requirements, such as employer-sponsored coverage, Medigap, or Medicaid. By law, beneficiary cost-sharing liability for a Part B drug or other service provided in a hospital outpatient setting on a single day cannot exceed the amount of the Part A hospital inpatient deductible, which is $1,676 in 2025. But this cap does not apply to Part B drugs administered in a physician’s office, and there is no limit on total annual out-of-pocket liability for services covered under Part A or Part B in traditional Medicare.

- Under Medicare Advantage, plans can charge no more than 20% for Part B drugs administered by an in-network provider and are required to have a maximum out-of-pocket limit, unlike traditional Medicare. In 2025, the limit averages $5,320 for in-network services and $9,547 for in-network and out-of-network services combined.

- Under Medicare Part D, coinsurance for high-priced drugs placed on the specialty tier, like Jakafi and Venclexta, ranges from 25% to 33%. Under the Part D benefit, an annual out-of-pocket spending cap of $2,000 in 2025 (increasing to $2,100 in 2026) limits an enrollee’s cost exposure, and another feature allows enrollees to spread out their out-of-pocket costs over the course of the calendar year, helping to limit the financial burden of high monthly cost-sharing requirements.

Based on these cost-sharing requirements, Medicare beneficiaries will face relatively high coinsurance for these orphan drugs each time the drug is administered or when they fill a prescription. For Part B drugs, out-of-pocket liability per claim can amount to $1,000 or more for drugs administered in a physician’s office or maxes out at the amount of the Part A inpatient deductible for drugs administered in hospital outpatient departments. For Part D drugs, beneficiaries in 2026 would likely hit the $2,100 out-of-pocket cap with a single prescription fill.

For example, based on the $12,600 total cost per claim for Keytruda in 2023, 20% coinsurance under Part B amounts to around $2,500, or roughly $15,000 for the year (based on six claims for each Keytruda user in 2023, on average). For Opdivo, coinsurance of 20% based on a $10,500 cost per claim amounts to $2,100 beneficiary liability per claim, or roughly $14,000 annually (based on 6.6 claims for each Opdivo user in 2023) (Figure 3). For Jakafi, the $16,700 total cost per claim would mean a Part D enrollee would hit the $2,100 annual out-of-pocket cap in 2026 with one fill, based on a specialty tier coinsurance requirement of 25% to 33%.

Additional delays and exclusions from Medicare drug price negotiation provided under the new tax and budget law will likely mean higher out-of-pocket costs for Medicare beneficiaries who use these medications

Medicare’s negotiated drug prices can help to lower the amount beneficiaries pay, particularly in situations where they face a coinsurance requirement that is calculated based on the underlying price of the drug, such as in the case of Part B drugs and higher-cost Part D drugs. By delaying price negotiation for certain orphan drugs or excluding them from eligibility for negotiation, the tax and budget law maintains higher prices relative to the price Medicare would have paid if the drugs had been eligible for drug price negotiation. The result will be higher out-of-pocket liability for Medicare beneficiaries, which could give rise to cost-related access problems and lower utilization.

Estimating the exact magnitude of higher cost-sharing liability would depend in part on how much lower Medicare’s negotiated prices would fall below status quo prices for drugs that would have been selected for negotiation but for the changes in law, and how much longer the higher prices apply. In the absence of these more exact estimates, the following examples of potential savings from Medicare drug price negotiation help to illustrate the potential foregone savings for beneficiaries of delaying or fully exempting orphan drugs from price negotiation.

- If the government were to negotiate a 22% discount off the price of Keytruda, on par with the average 22% net price discount from the first round of Medicare drug price negotiation, that would generate savings of around $550 per claim for Medicare beneficiaries, reducing out-of-pocket liability to just under $2,000. Annual savings would amount to around $3,300, based on an average of six claims per user in 2023.

- Similarly, for Opdivo, a 22% negotiated price discount would generate savings of around $460 per claim, reducing out-of-pocket liability to around $1,600. Annual savings would amount to around $3,000, based on an average of 6.6 claims per Opdivo user in 2023.

These illustrative examples suggest that the continuation of higher prices for certain drugs brought about by the new tax and budget law could place additional financial strain on beneficiaries in the form of higher out-of-pocket liability, with potential out-of-pocket savings from price negotiation for these high-cost drugs of several hundred dollars. At the same time, even reduced cost-sharing liability for these expensive medications might continue to represent a substantial financial burden for some Medicare beneficiaries, especially for those in traditional Medicare without additional coverage and those in Medicare Advantage prior to reaching their maximum out-of-pocket limit.

Delaying or excluding additional orphan drugs from selection for Medicare drug price negotiation will cost the federal government several billion dollars over the coming decade

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) initially estimated that changes to the orphan drug exclusion in the new tax and budget law would increase Medicare spending by $4.9 billion between 2028 and 2034. However, this amount is likely an underestimate of the spending impact since CBO reportedly did not fully account for certain drugs in its initial estimate, including Keytruda, and is said to be reevaluating the cost impact of these changes. This amount could also grow over time based on how the pharmaceutical industry responds in terms of changes in orphan drug research and development and the pipeline of new drugs coming to market and changing incentives around seeking additional orphan indications (as well as non-orphan indications) for orphan drugs already on the market.

With several blockbuster drugs expected to be delayed or excluded from selection for negotiation due to the changes in the new tax and budget law, CMS will be required to skip over these higher-spending drugs when it selects the list of drugs for negotiation in the future. While the changes to the IRA’s orphan drug exclusion were made in response to claims about the potential for less innovation related to drugs for rare diseases under the original provision, the changes are expected to reduce the potential savings from Medicare’s drug price negotiation program and prolong higher out-of-pocket liability for Medicare patients who use these drugs.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.