Simi Jolaoso,

Jack Goodmanand

Sarah Buckley,BBC Eye Investigations

Chance Letikva

Chance LetikvaWarning: Disturbing content

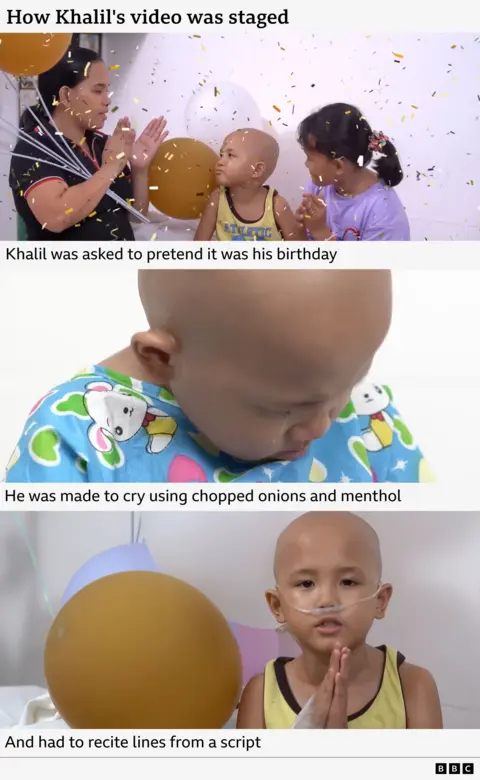

A little boy faces the camera. He is pale and has no hair.

“I am seven years old and I have cancer,” he says. “Please save my life and help me.”

Khalil – who is pictured above in a still from the film – didn’t want to record this, says his mother Aljin. She had been asked to shave his head, and then a film crew hooked him up to a fake drip, and asked his family to pretend it was his birthday. They had given him a script to learn and recite in English.

And he didn’t like it, says Aljin, when chopped onions were placed next to him, and menthol put under his eyes, to make him cry.

Aljin agreed to it because, although the set-up was fake, Khalil really did have cancer. She was told this video would help crowdfund money for better treatment. And it did raise funds – $27,000 (£20,204), according to a campaign we found in Khalil’s name.

But Aljin was told the campaign had failed, and says she received none of this money – just a $700 (£524) filming fee on the day. One year later, Khalil died.

Across the world, desperate parents of sick or dying children are being exploited by online scam campaigns, the BBC World Service has discovered. The public have given money to the campaigns, which claim to be fundraising for life-saving treatment. We have identified 15 families who say they got little to nothing of the funds raised and often had no idea the campaigns had even been published, despite undergoing harrowing filming.

Nine families we spoke to – whose campaigns appear to be products of the same scam network – say they never received anything at all of the $4m (£2.9m) apparently raised in their names.

A whistleblower from this network told us they had looked for “beautiful children” who “had to be three to nine years old… without hair”.

We have identified a key player in the scam as an Israeli man living in Canada called Erez Hadari.

Our investigation began in October 2023, when a distressing YouTube advert caught our attention. “I don’t want to die,” a girl called Alexandra from Ghana sobbed. “My treatments cost a lot.”

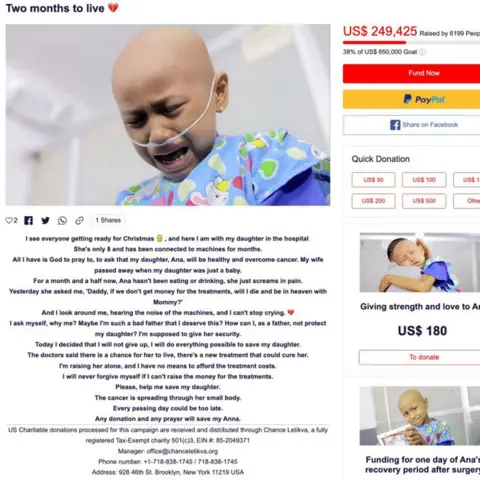

A crowdfunding campaign for her appeared to have raised nearly $700,000 (£523,797).

We saw more videos of sick children from around the world on YouTube, all strikingly similar – slickly produced, and seemingly having raised huge amounts of money. They all conveyed a sense of urgency, using emotive language.

We decided to investigate further.

The campaigns with the biggest apparent international reach were under the name of an organisation called Chance Letikva (Chance for Hope, in English) – registered in Israel and the US.

Identifying the children featured was difficult. We used geolocation, social media and facial recognition software to find their families, based as far apart as Colombia and the Philippines.

Chance Letikva

Chance LetikvaWhile it was difficult to know for sure if the campaign websites’ cash totals were genuine, we donated small amounts to two of them and saw the totals increase by those amounts.

We also spoke to someone who says she gave $180 (£135) to Alexandra’s campaign and was then inundated with requests for more, all written as if sent by Alexandra and her father.

In the Philippines, Aljin Tabasa told us her son Khalil had fallen ill just after his seventh birthday.

“When we found out it was cancer it felt like my whole world shattered,” she says.

Aljin says treatment at their local hospital in the city of Cebu was slow, and she had messaged everyone she could think of for help. One person put her in touch with a local businessman called Rhoie Yncierto – who asked for a video of Khalil which, looking back, Aljin realises was essentially an audition.

Another man then arrived from Canada in December 2022, introducing himself as “Erez”. He paid her the filming fee up front, she says, promising a further $1,500 (£1,122) a month if the film generated lots of donations.

Erez directed Khalil’s film at a local hospital, asking for retake after retake – the shoot taking 12 hours, Aljin says.

Months later, the family say they had still not heard how the video had performed. Aljin messaged Erez, who told her the video “wasn’t successful”.

“So as I understood it, the video just didn’t make any money,” she says.

But we told her the campaign had apparently collected $27,000 (£20,204) as of November 2024, and was still online.

“If I had known the money we had raised, I can’t help but think that maybe Khalil would still be here,” Aljin says. “I don’t understand how they could do this to us.”

When asked about his role in the filming, Rhoie Yncierto denied telling families to shave their children’s heads for filming and said he had received no payment for recruiting families.

He said he had “no control” over what happened with the funds and had no contact with the families after the day of filming. When we told him they had not received any of the campaigns’ donations he said he was “puzzled” and was “very sorry for the families”.

Nobody named Erez appears on registration documents for Chance Letikva. But two of its campaigns we investigated had also been promoted by another organisation called Walls of Hope, registered in Israel and Canada. Documents list the director in Canada as Erez Hadari.

Photos of him online show him at Jewish religious events in the Philippines, New York and Miami. We showed Aljin, and she said it was the same person she had met.

We asked Mr Hadari about his involvement in a campaign in the Philippines. He did not respond.

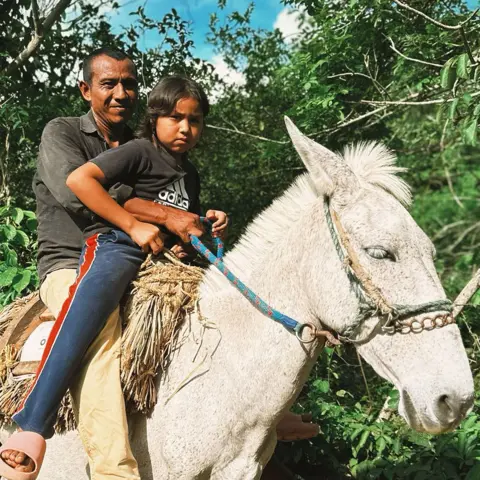

We visited further families whose campaigns were either organised by, or linked to, Mr Hadari – one in a remote indigenous community in Colombia, and another in Ukraine.

As with Khalil’s case, local fixers had got in touch to offer help. The children were filmed and made to cry or fake tears for a nominal fee, but never received any further money.

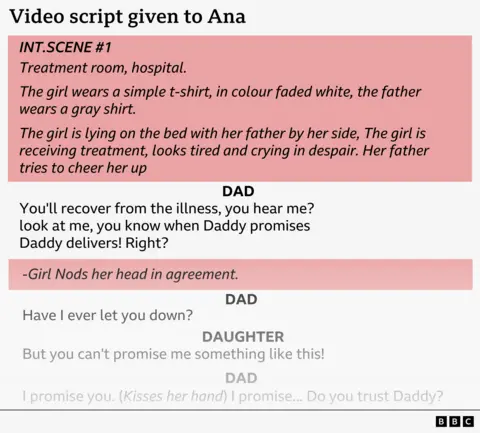

In Sucre, north-west Colombia, Sergio Care says he initially refused this help. He had been approached by someone called Isabel, he says, who offered financial assistance after his eight-year-old daughter, Ana, was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumour.

But Isabel came looking for him at the hospital treating Ana, he says, accompanied by a man who said he worked for an international NGO.

The description Sergio gave of the man matched that of Erez Hadari – he then recognised him in a photo we showed him.

“He gave me hope… I didn’t have any money for the future.”

Demands on the family did not end with the filming.

Isabel kept ringing, Sergio says, demanding more photos of Ana in hospital. When Sergio didn’t reply, Isabel started messaging Ana herself – voice notes we have heard.

Ana told Isabel she had no more photos to send. Isabel replied: “This is very bad Ana, very bad indeed.”

In January this year, Ana – now fully recovered – tried to find out what happened to the money promised.

“That foundation disappeared,” Isabel told her in a voice note. “Your video was never uploaded. Never. Nothing was done with it, you hear?”

But we could see the video had been uploaded and, by April 2024, appeared to have raised nearly $250,000 (£187,070).

In October, we persuaded Isabel Hernandez to speak to us over video link.

A friend from Israel, she explained, had introduced her to someone offering work for “a foundation” looking to help children with cancer. She refused to name who she worked for.

She was told only one of the campaigns she helped organise was published, she says, and that it had not been successful.

We showed Isabel that two campaigns had in fact been uploaded – one of them apparently raising more than $700,000 (£523,797).

“I need to apologise to [the families],” she said. “If I’d known what was going on, I would not have been able to do something like this.”

In Ukraine, we discovered that the person who approached the mother of a sick child was actually employed in the place where the campaign video was filmed.

Tetiana Khaliavka organised a shoot with five-year-old Viktoriia, who has brain cancer, at Angelholm Clinic in Chernivtsi.

One Facebook post linked to Chance Letikva’s campaign shows Viktoriia and her mother Olena Firsova, sitting on a bed. “I see your efforts to save my daughter, and it deeply moves us all. It’s a race against time to raise the amount needed for Viktoriia’s treatments,” reads the caption.

Olena says she never wrote or even said these words and had no idea the campaign had been uploaded.

It appears to have raised more than €280,000 (£244,000).

Tetiana, we were told, was in charge of advertising and communications at Angelholm.

The clinic recently told the BBC it didn’t approve filming on its premises – adding: “The clinic has never participated in, nor supported, any fundraising initiatives organised by any organisation.”

Angelholm says it has terminated Tetiana Khaliavka’s employment.

Olena showed us the contract she had been asked to sign.

In addition to the family’s $1,500 (£1,122) filming fee on the day, it states they would get $8,000 (£5,986) once the fundraising goal was met. The amount for the goal, however, has been left blank.

The contract showed an address in New York for Chance Letikva. On the organisation’s website, there is another – in Beit Shemesh, about an hour from Jerusalem. We travelled to both, but found no sign of it.

And we discovered Chance Letikva seems to be one of many such organisations.

The man who filmed Viktoriia’s campaign told our producer – who was posing as a friend of a sick child – that he works for other similar organisations.

“Each time, it’s a different one,” the man – who had introduced himself as “Oleh” – told her. “I hate to put it this way, but they work kind of like a conveyor belt.”

“About a dozen similar companies” requested “material”, he said, naming two of them – Saint Teresa and Little Angels, both registered in the US.

When we checked their registration documents, we once again found Erez Hadari’s name.

What is not clear is where the money raised for the children has gone.

More than a year after Viktoriia’s filming, her mother Olena rang Oleh, who seems to go by Alex Kohen online, to find out. Shortly afterwards, someone from Chance Letikva called to say the donations had paid for advertising, she says.

This is also what Mr Hadari told Aljin, Khalil’s mother, when she confronted him over the phone.

“There is cost of advertising. So the company lost money,” Mr Hadari told her, without giving any evidence to support this.

Charity experts told us advertising should not amount to more than 20% of the total raised by campaigns.

Someone previously employed to recruit children for Chance Letikva campaigns told us how those featured had been chosen.

They had been asked to visit oncology clinics, they said – speaking on condition of anonymity.

“They were always looking for beautiful children with white skin. The child had to be three to nine years old. They had to know how to speak well. They had to be without hair,” they told us.

“They asked me for photos, to see if the child is right, and I would send it to Erez.”

The whistleblower told us Mr Hadari would then send the photo on to someone else, in Israel, whose name they were never told.

As for Mr Hadari himself, we tried to reach him at two addresses in Canada but could not find him. He replied to one voice note we had sent him – asking about the money he had been apparently crowdfunding – by saying the organisation “has never been active”, without specifying which one. He did not respond to a further voice note and letter laying out all our questions and allegations.

Erez Hadari

Erez HadariCampaigns set up by Chance Letikva for two children who died – Khalil and a Mexican boy called Hector – still appear to be accepting money.

Chance Letikva’s US branch appears to be linked to a new organisation called Saint Raphael, which has produced more campaigns – at least two of which seem to have been filmed in Angelholm clinic in Ukraine, as the clinic’s distinctive wood panelling and staff uniforms can be seen.

Olena, Viktoriia’s mother, says her daughter has been diagnosed with another brain tumour. She says she is sickened by the findings of our investigation.

“When your child is… hanging on the edge of life, and someone’s out there, making money off that. Well, it’s filthy. It’s blood money.”

The BBC contacted Tetiana Khaliavka and Alex Kohen, and the organisations Chance Letikva, Walls of Hope, Saint Raphael, Little Angels and Saint Teresa – inviting them to respond to the allegations made against them. None of them replied.

The Israeli Corporations Authority, which oversees the country’s non-profit organisations, told us that if it has evidence founders are using entities as “a cover for illegal activity”, then registration inside Israel may be denied and the founder could be barred from working in the sector.

UK regulator, the Charity Commission, advises those wishing to donate to charities to check that those associations are registered, and that the appropriate fundraising regulator should be contacted if in doubt.

Additional reporting by: Ned Davies, Tracks Saflor, Jose Antonio Lucio, Almudena Garcia-parrado, Vitaliya Kozmenko, Shakked Auerbach, Tom Tzur Wisfelder, Katya Malofieieva, Anastasia Kucher, Alan Pulido and Neil McCarthy

- If you have any information to add to this investigation please contact simi@bbc.co.uk