GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) drugs were originally developed to help people with type 2 diabetes manage blood sugar levels but have gained widespread attention for their effectiveness as a treatment for obesity. Due to their cost, however, coverage of GLP-1s for obesity treatment in Medicaid, ACA Marketplace plans, and most large employer firms remains limited, and GLP-1 coverage in Medicare for treatment of obesity is prohibited under current law. While state Medicaid programs must cover nearly all Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs, a long-standing statutory exception allows states to choose whether to cover weight-loss drugs under Medicaid. As a result, Medicaid coverage of GLP-1 drugs for obesity treatment is optional for states, while coverage for other indications (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and sleep apnea) is required.

The upfront costs of GLP-1s are an ongoing concern for both public and private payers, and some employers and state Medicaid programs are now restricting coverage, despite recognizing their effectiveness at treating obesity. Expanded obesity drug coverage can increase Medicaid spending and put pressure on overall state budgets, and states are now facing tighter budget conditions and longer-term fiscal uncertainty, due in part to the federal Medicaid cuts in the 2025 reconciliation law, causing state Medicaid programs to re-evaluate their obesity drug coverage. However, almost four in ten adults and a quarter of children with Medicaid have obesity, meaning expanding Medicaid coverage of these drugs could provide access to effective obesity treatments for millions. In the longer term, reduced obesity rates among Medicaid enrollees could also result in reduced Medicaid spending on chronic diseases associated with obesity, though the evidence is mixed. Any savings on health spending because of obesity drugs may take many years and may not accrue to the Medicaid program if individuals experience shifts in coverage, so states may not be factoring long-term savings into coverage decisions.

At the federal level, the Trump administration decided not to proceed with a Biden administration proposal to allow Medicare and require Medicaid to cover obesity drugs but recently launched their own obesity drug coverage initiatives to reduce costs and increase access (see Box 1). While lower prices for state Medicaid programs could help alleviate cost concerns for states and result in expanded coverage of obesity drugs, how the new lower costs compare to the net prices state Medicaid programs currently pay and how states will respond amid tightening budget conditions remain unclear. Further, the recent announcements will not impact costs for Medicaid enrollees as they already pay little or no copays for prescription drugs, and the costs of purchasing drugs directly from manufacturers through TrumpRx will likely still be prohibitive for people on Medicaid who must have a low income to qualify for the program. Unless Medicaid covers obesity medications, enrollees are unlikely to have access to them given the high out-of-pocket cost even at lower prices.

This brief discusses the current landscape of Medicaid GLP-1 coverage and examines recent trends in Medicaid prescriptions and gross spending on GLP-1s. Key takeaways include:

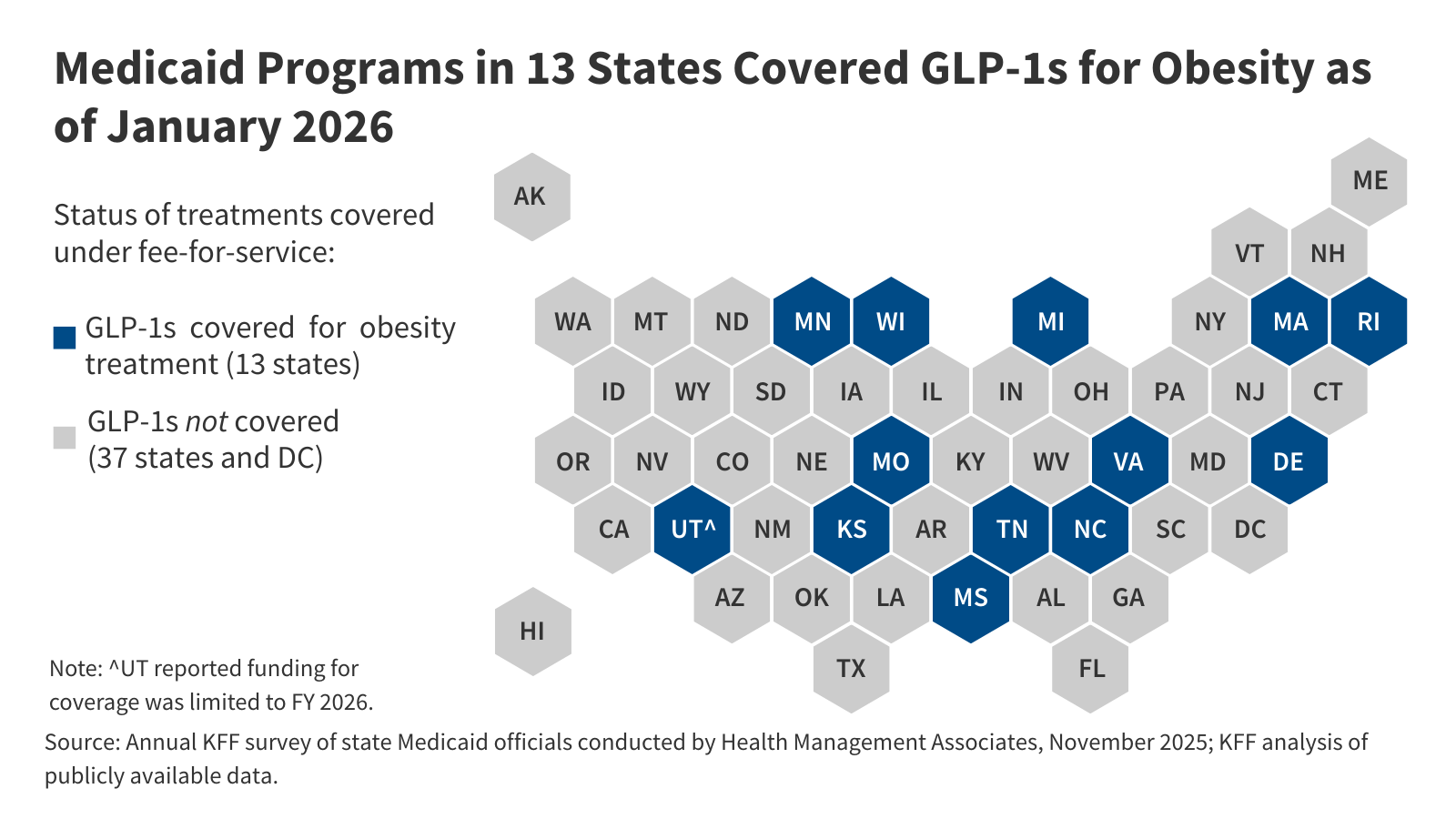

- Obesity drug coverage in Medicaid remains limited, with 13 state Medicaid programs covering GLP-1s for obesity treatment under fee-for-service (FFS) as of January 2026.

- The number of Medicaid prescriptions and gross spending on GLP-1s have both increased substantially since 2019.

- Increased utilization of Ozempic and Wegovy (semaglutide) as well as Mounjaro and Zepbound (tirzepatide) have contributed substantially to recent growth.

Box 1: Recent Trump Administration Obesity Drug Initiatives

In November 2025, the Trump administration announced reaching a deal with Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk to lower the cost of their GLP-1s for Medicare, Medicaid, and those purchasing the drugs directly from the manufacturers through a new TrumpRx website. In December 2025, the administration also introduced the BALANCE (Better Approaches to Lifestyle and Nutrition for Comprehensive hEalth) model, a five year CMS Innovation Center (CMMI) model that intends to expand access to obesity drugs in Medicaid and Medicare by negotiating lower GLP-1 prices with manufacturers. The new model will include standardized coverage criteria as well as lifestyle supports and is voluntary for state Medicaid programs, Medicare Part D plans, and manufacturers. State Medicaid programs and manufacturers were requested to submit their intentions to participate by January 8, 2026, and the model is expected to begin in May 2026. For Medicare Part D, this model will be implemented in January 2027, following a separate short-term demonstration that will allow Medicare Part D enrollees to access obesity drugs beginning in July 2026.

Does Medicaid cover GLP-1s for obesity treatment?

States can decide whether to cover obesity drugs under Medicaid. Under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, Medicaid programs must cover nearly all of a participating manufacturer’s FDA-approved drugs for medically accepted indications. However, weight-loss drugs are included in a small group of drugs that can be excluded from coverage1 (though the statutory exception refers to agents used for “weight loss”, “obesity drugs” is used to refer to this group of medications in this analysis). As a result, coverage of GLP-1 drugs for the treatment of obesity remains optional for states, while coverage is required for drugs approved for the treatment of diabetes and, since March 2024 and December 2024, for the treatment of cardiovascular disease (Wegovy) and moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea in adults with obesity (Zepbound), respectively (Table 1). Coverage is also required if deemed medically necessary for children under Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit.

Obesity drug coverage in Medicaid remains limited, with 13 state Medicaid programs covering GLP-1s for obesity treatment under FFS as of January 2026 (Figure 1). When covered, GLP-1s are typically subject to utilization controls such as prior authorization, which can further limit access. Notably, KFF’s 2025 Medicaid budget survey found 16 state Medicaid programs covered GLP-1s for obesity treatment as of October 2025; however, since then, four states (California, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina) have eliminated coverage of GLP-1s for obesity treatment, likely reflecting recent state budget challenges and the significant costs associated with coverage. North Carolina eliminated GLP-1 coverage beginning October 2025 due to a budget stalemate in the legislature, but coverage was reinstated in December 2025, bringing the total number of states covering GLP-1s for obesity to 13 as of January 2026. A few other states are planning or considering obesity drug restrictions in state fiscal year 2026 or 2027, and state interest in expanding coverage of obesity drugs is also waning according to this year’s survey, with states continuing to report cost as the key factor contributing to obesity drug coverage decisions. The state obesity drug coverage landscape will continue to evolve as states respond to the recent announcement of the BALANCE model (see Box 1) and as states contend with budget challenges and the federal Medicaid spending cuts in the 2025 reconciliation law.

How have Medicaid prescriptions and gross spending on GLP-1s changed in recent years?

The number of Medicaid prescriptions and gross spending on GLP-1s have increased substantially since 2019 (Figure 2). Not all GLP-1s are approved for obesity treatment, and this analysis includes all FDA-approved GLP-1s, including those approved for obesity (Saxenda, Weogvy, Zepbound) as well as those approved for type 2 diabetes (see Table 1). Overall, the number of GLP-1 prescriptions increased sevenfold, from about 1 million in 2019 to over 8 million in 2024. At the same time, gross spending increased ninefold, from about $1 billion in 2019 to almost $9 billion in 2024, and gross spending per GLP-1 prescription reached $1,000 in 2024. Preliminary trends through June 2025 (data not shown) show rapid growth will continue in 2025. Those prices and spending numbers do not account for rebates, and states typically receive substantial rebates on brand drugs. In response to growing criticism of the cost of their drugs, Novo Nordisk, the company that manufactures Ozempic and Wegovy, reported last year that rebates and other fees (across all payers) accounted for about 40% of the cost of the two drugs and that they expected rebates to grow. GLP-1s still account for a relatively small share of the total number of Medicaid prescriptions, accounting for about 1% of all Medicaid prescriptions in 2024 (up from about 0% in 2019). However, GLP-1s accounted for over 8% of all Medicaid prescription drug spending before rebates in 2024 (up from 1% in 2019).

Specifically, increased utilization of Ozempic and Wegovy (semaglutide) as well as Mounjaro and Zepbound (tirzepatide) have contributed substantially to recent growth. Prescriptions and spending on Ozempic, approved for type 2 diabetes (not obesity) in 2017, have grown considerably over the period. By 2024, Ozempic had surpassed Trulicity, also approved for type 2 diabetes (not obesity) to make up the largest share of GLP-1 prescriptions and spending (39% in 2024). Looking from 2023 to 2024, the latest year of data available, prescriptions and gross spending for Wegovy (first approved for obesity in 2021, approved for cardiovascular disease in 2024) and Mounjaro (approved for type 2 diabetes in 2022) more than doubled, and prescriptions and gross spending for Zepbound (first approved for obesity in 2023, approved for sleep apnea in 2024) increased more than fivefold. These drugs are produced by Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, which both recently announced agreements with the Trump administration to lower prices. From Medicaid data publicly available, there is no way yet to disentangle how much of the growing use of GLP-1s is related to treatment for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or sleep apnea versus obesity, or a combination.

Methods

Number of Prescriptions and Gross Spending Data: This analysis uses 2019 through 2024 State Drug Utilization Data (SDUD) (downloaded in January 2026). The SDUD is publicly available data provided as part of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), and provides information on the number of prescriptions, Medicaid spending before rebates, and cost-sharing for rebate-eligible Medicaid outpatient drugs by NDC, quarter, managed care or fee-for-service, and state. It also provides this data summarized for the whole country. The data do not include information on the number of days supplied in each prescription. CMS has suppressed SDUD cells with fewer than 11 prescriptions, citing the Federal Privacy Act and the HIPAA Privacy Rule. This analysis used the national totals data because less data is suppressed at the national versus state level.

Identifying GLP-1s: This analysis includes all Medicaid prescriptions and gross spending for any FDA-approved GLP-1s. KFF links each drug’s NDC in the dataset to a drug class using the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. GLP-1s are then identified as those classified under “A10BJ” or glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogues. The analysis also includes tirzepatide (Mounjaro and Zepbound), which is a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 agonist (and classified under “A10BX” or other blood glucose lowering drugs, excl. insulins). This method results in the inclusion of Medicaid prescriptions and gross spending for: Ozempic, Rybelsus, Mounjaro, Victoza, Trulicity, Wegovy, Zepbound, Saxenda, and generic liraglutide as well as a small number of prescriptions and spending for Adlyxin, Byetta, Bydureon BCise, and Tanzeum (now discontinued).

Limitations: There are a few limitations to the estimates of Medicaid prescriptions and gross spending found in this analysis, including:

- This analysis examines the number of Medicaid prescriptions in the data and does not adjust for days supplied by each prescription.

- Gross spending and spending per prescription numbers do not account for rebates.

- The SDUD are updated quarterly; a new quarter of data is typically released, and the prior five years of data are also updated. This means utilization and gross spending totals can vary depending on when the data is downloaded, and totals may not match other outside sources or prior KFF analysis for this reason.