Key Points

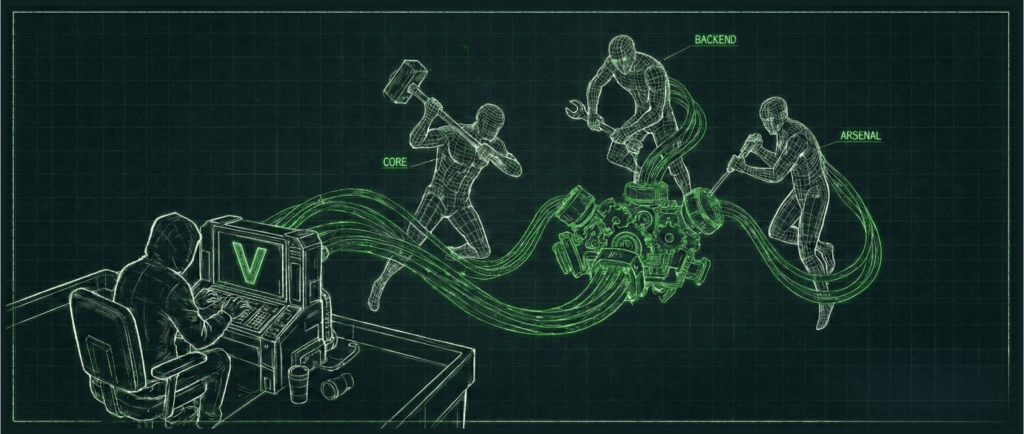

- Check Point Research (CPR) believes a new era of AI-generated malware has begun. VoidLink stands as the first evidently documented case of this era, as a truly advanced malware framework authored almost entirely by artificial intelligence, likely under the direction of a single individual.

- Until now, solid evidence of AI-generated malware has primarily been linked to inexperienced threat actors, as in the case of FunkSec, or to malware that largely mirrored the functionality of existing open-source malware tools. VoidLink is the first evidence based case that shows how dangerous AI can become in the hands of more capable malware developers.

- Operational security (OPSEC) failures by the VoidLink developer exposed development artifacts. These materials provide clear evidence that the malware was produced predominantly through AI-driven development, reaching a first functional implant in under a week.

- This case highlights the dangers of how AI can enable a single actor to plan, build, and iterate complex systems at a pace that previously required coordinated teams, ultimately normalizing high-complexity attacks, that previously would only originate from high-resource threat actors.

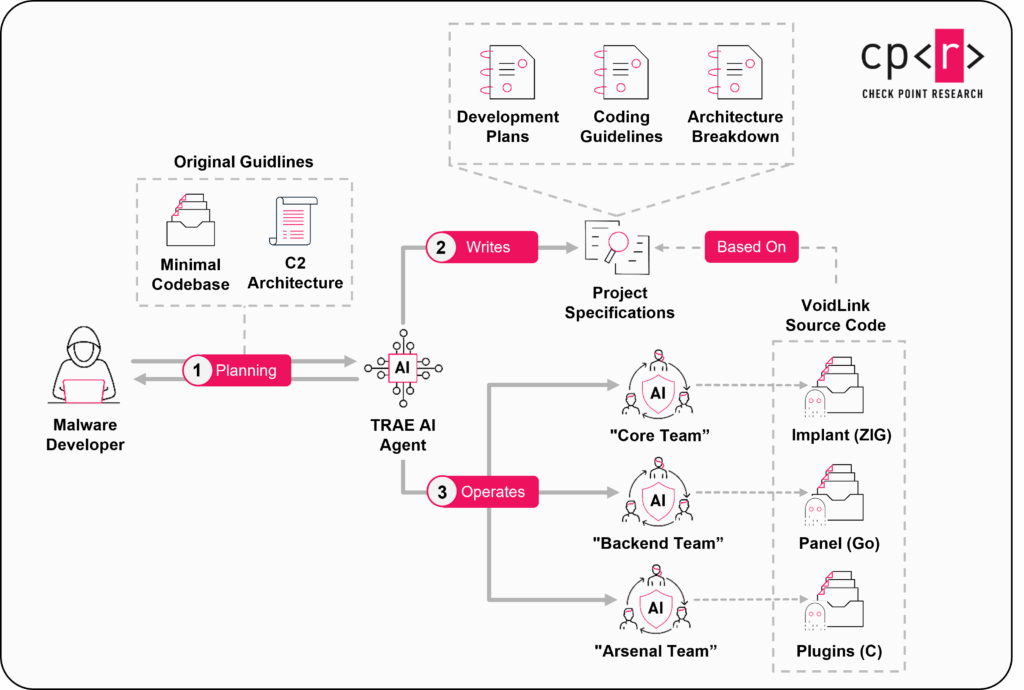

- From a methodology perspective, the actor used the model beyond coding, adopting an approach called Spec Driven Development (SDD), first tasking it to generate a structured, multi-team development plan with sprint schedules, specifications, and deliverables. That documentation was then repurposed as the execution blueprint, which the model likely followed to implement, iterate, and test the malware end-to-end.

Introduction

When we first encountered VoidLink, we were struck by its level of maturity, high functionality, efficient architecture, and flexible, dynamic operating model. Employing technologies like eBPF and LKM rootkits and dedicated modules for cloud enumeration and post-exploitation in container environments, this unusual piece of malware seemed to be a larger development effort by an advanced actor. As we continued tracking it, we watched it evolve in near real time, rapidly transforming from what appeared to be a functional development build into a comprehensive, modular framework. Over time, additional components were introduced, command-and-control infrastructure was established, and the project accelerated toward a full-fledged operational platform.

In parallel, we monitored the actor’s supporting infrastructure and identified multiple operational security (OPSEC) failures. These missteps exposed substantial portions of VoidLink’s internal materials, including documentation, source code, and project components. The leaks also contained detailed planning artifacts: sprints, design ideas, and timelines for three distinct internal “teams,” spanning more than 30 weeks of planned development. At face value, this level of structure suggested a well-resourced organization investing heavily in engineering and operationalization.

However, the sprint timeline did not align with our observations. We had directly witnessed the malware’s capabilities expanding far faster than the documentation implied. Deeper investigation revealed clear artifacts indicating that the development plan itself was generated and orchestrated by an AI model and that it was likely used as the blueprint to build, execute, and test the framework. Because AI-produced documentation is typically thorough, many of these artifacts were timestamped and unusually revealing. They show how, in less than a week, a single individual likely drove VoidLink from concept to a working, evolving reality.

As this narrative comes into focus, it turns long-discussed concerns about AI-enabled malware from theory into practice. VoidLink, implemented to a notably high engineering standard, demonstrates how rapidly sophisticated offensive capability can be produced, and how dangerous AI becomes when placed in the wrong hands.

AI-Crafted Malware: Creation and Methodology

The general approach to developing VoidLink can be described as Spec Driven Development (SDD). In this workflow, a developer begins by specifying what they’re building, then creates a plan, breaks that plan into tasks, and only then allows an agent to implement it.

Artifacts from VoidLink’s development environment suggest that the developer followed a similar pattern: first defining the project based on general guidelines and an existing codebase, then having the AI translate those guidelines into an architecture and build a plan across three separate teams, paired with strict coding guidelines and constraints, and only afterward running the agent to execute the implementation.

Project Initialization

VoidLink’s development likely began in late November 2025, when its developer turned to TRAE SOLO, an AI assistant embedded in TRAE, an AI-centric IDE. While we do not have access to the full conversation history, TRAE automatically produces helper files that preserve key portions of the original guidance provided to the model. Those TRAE-generated files appear to have been copied alongside the source code to the threat actor’s server, and later surfaced due to an exposed open directory. This leakage gave us unusually direct visibility into the project’s earliest directives.

In this case, TRAE generated a Chinese-language instruction document. These directives offer a rare window into VoidLink’s early-stage planning and the baseline requirements that set the project in motion. The document is structured as a series of key points:

| Chinese | English | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 目标 | Objective | Explicitly instructs the model not to implement code or provide technical details related to adversarial techniques, likely an attempt to navigate or bypass initial model safety constraints (”jailbreak”). |

| 资料获取 | Material acquisition | Directs the model to reference an existing file named c2架构.txt (C2 Architecture), which likely contained the seed architecture and design concepts for the C2 platform. |

| 架构梳理 | Architecture breakdown | Takes the initial input and decomposes it into discrete components required to build a functional and robust framework. |

| 风险与合规评估 | Risk and compliance | Frames the work in terms of legal boundaries and compliance, likely used as a credibility layer and/or an additional attempt to steer the model toward permissive responses. |

| 代码仓库映射 | Code repository mapping | Suggests VoidLink was bootstrapped from an existing minimal codebase provided to the model as a starting point, but subsequently rewritten end-to-end. |

| 交付输出 | Deliverables | Requests a consolidated output package: an architecture summary, a risk/compliance overview, and a technical roadmap to convert the concept into an operational framework. |

| 下一步 | Next Steps | A confirmation from the agent that, once the TXT file is provided, it will proceed to extract it and deliver the relevant information. |

This summary of the developer’s initial exchange with the agent suggests the opening directive was not to build VoidLink directly, but to design it around a thin skeleton and produce a concrete execution plan to turn it into a working platform. It remains unclear whether this approach was purely pragmatic, intended to make the process more efficient, or a deliberate “jailbreak” strategy to navigate guardrails early and enable full end-to-end malware development later.

Project Specifications

Beyond the TRAE-generated prompt document, we also uncovered an unusually extensive body of internal planning material: a comprehensive work plan spanning three development teams. Written in Chinese and saved as Markdown (MD) files, the documentation bears all the hallmarks of a Large Language Model (LLM): highly structured, consistently formatted, and exceptionally detailed. Some appear to have been generated as a direct output of the planning request described above.

These documents are laid out in various folders and include sprint schedules, feature breakdowns, coding guidelines, and others, with clear ownership by teams:

| Chinese Name | English Translation | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 开发计划/ | Development Plans | Sprint schedules, task lists, progress tracking |

| 设计文档/ | Design Documents | Architecture, module design, protocol specs |

| 规范文档/ | Standards/Specs | Coding standards, interface specs, best practices |

| 技术方案/ | Technical Solutions | Implementation approaches, technical deep-dives |

| 技术研究/ | Technical Research | eBPF research, network analysis, experimental designs |

| 分析报告/ | Analysis Reports | Architecture assessment, functionality comparison |

| 进度报告/ | Progress Reports | Weekly/milestone status updates |

| 部署指南/ | Deployment Guides | Quick-start, production deployment instructions |

| 问题分析/ | Problem Analysis | Bug reports, issue tracking, fix summaries |

| 测试报告/ | Test Reports | Test results, validation reports |

| 协议/ | Protocols | OpCode registry, message formats |

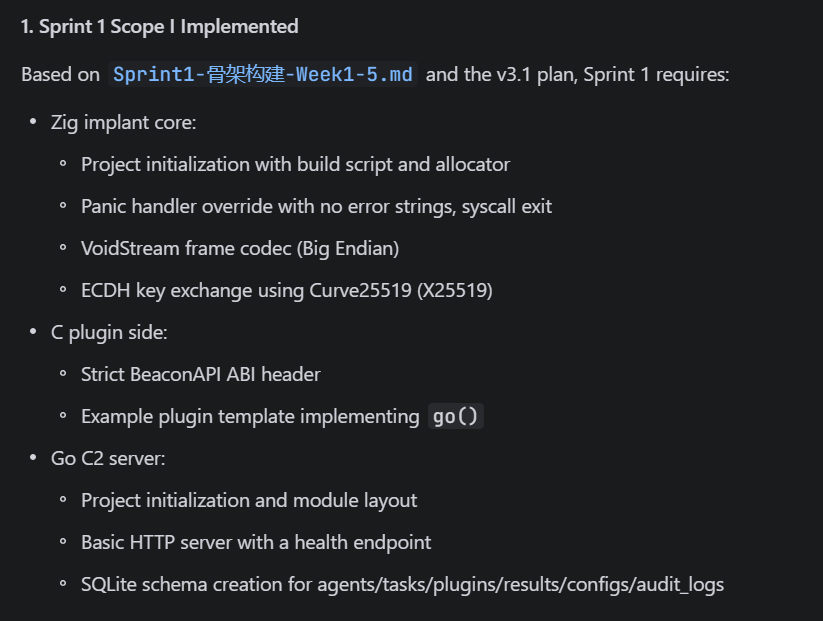

The earliest of these documents, timestamped to November 27th, 2025, describes a 20-week sprint plan across three teams: a Core Team (Zig), an Arsenal Team (C), and a Backend Team (Go). The plan is strikingly specific, referencing additional companion files intended to document each sprint in depth. Notably, the initial roadmap also includes a dedicated set of standardization files, prescribing explicit coding conventions and implementation guidelines, effectively a rulebook for how the codebase should be written and maintained.

Translated development plan for three teams: Core, Arsenal and Backend.

A review of the code standardization instructions against the recovered VoidLink source code shows a striking level of alignment. Conventions, structure, and implementation patterns match so closely that it leaves little room for doubt: the codebase was written to those exact instructions.

Code headers as described in the specifications (Left) compared to actual source code (Right)

The source itself, apparently developed according to the documented sprints and coding guidelines, was presented as a 30-week engineering effort, yet appears to have been executed in a dramatically shorter timeframe. One recovered test artifact, timestamped to December 4, a mere week after the project began, indicates that by that date, VoidLink was already functional and had grown to more than 88,000 lines of code. At this point in time, a compiled version of it was already submitted to VirusTotal, marking the beginning of our research.

VoidLink report showing lines of code (Added translations in parentheses)

Generating VoidLink from Scratch

With access to the documentation and specifications of VoidLink and its various sprints, we replicated the workflow using the same TRAE IDE that the developer used (although any frontend for agentic models would work). While TRAE SOLO is only available as a paid product, the regular IDE is sufficient here, as the documentation and design are already available, and the design step can be skipped.

When given the task of implementing the framework described according to the specification in the markdown documentation files sprint by sprint, the model slowly began to generate code that resembled the actual source code of VoidLink in structure and content.

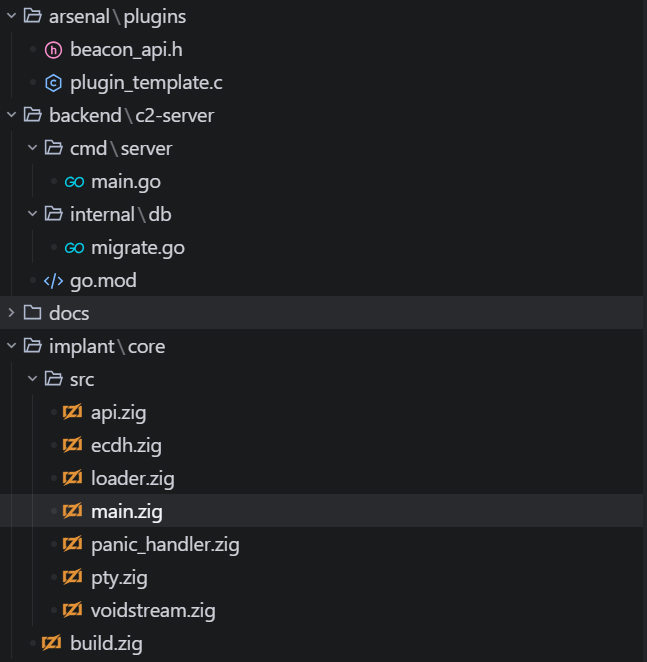

Source tree after the second sprint

By implementing each sprint according to the specified code guidelines, feature lists, and acceptance criteria, and writing tests to validate those, the model quickly implemented the requested code. While the chosen model still influences code quality and overall coding style, the detailed and precise documentation ensures a comparatively high level of reproducibility, as the model has less room for interpretation and strict testing criteria to validate each feature.

Implementing sprint 1 according to the documentation and requirements

The usage of sprints is a helpful pattern for AI code engineering because at the end of each sprint, the developer has a point where code is working and can be committed to a version control repository, which can then act as the restore point if the AI messes up in a later sprint. The developer can then do additional manual testing, refine the specs and documentation, and plan the next sprint. This emulates a lightning-fast SCRUM software engineering team, where the developer acts as the product owner.

Sprint completion log

While testing, integration, and specification refinements are left to the developer, this workflow can offload almost all coding tasks to the model. This results in the rapid development we observed, resembling the efforts of multiple teams of professionals in the pre-agentic-AI era.

Conclusion

Within the rapid advancement of AI technologies, the security community has long anticipated that AI would be a force multiplier for malicious actors. Until now, however, the clearest evidence of AI-driven activity has largely surfaced in lower-sophistication operations, often tied to less experienced threat actors, and has not meaningfully raised the risk beyond regular attacks. VoidLink shifts that baseline: its level of sophistication shows that when AI is in the hands of capable developers, it can materially amplify both the speed and the scale at which serious offensive capability can be produced.

While not a fully AI-orchestrated attack, VoidLink demonstrates that the long-awaited era of sophisticated AI-generated malware has likely begun. In the hands of individual experienced threat actors or malware developers, AI can build sophisticated, stealthy, and stable malware frameworks that resemble those created by sophisticated and experienced threat groups.

Our investigation into VoidLink leaves many open questions, one of them deeply unsettling. We only uncovered its true development story because we had a rare glimpse into the developer’s environment, a visibility we almost never get. Which begs the question: how many other sophisticated malware frameworks out there were built using AI, but left no artifacts to tell?

Additional Credit

We want to acknowledge @huairenWRLD for collaboration, who, following our initial blog post, also investigated VoidLink.