Egg cells don’t dispose of their waste the same way other cells do

Sebastian Kaulitzki / Alamy

Human eggs seem to dispose of their waste more slowly than other cells do, which may help them avoid wear and tear – and explain why they live longer.

Every woman is born with a finite number of egg cells, or oocytes, which need to survive for about five decades. For cells, that’s an unusually long time. Although some human cells, like those in the brain and eyes, can live as long as you do, most have much shorter lifespans, in part because the natural processes that allow them to function also damage them over time.

Cells must recycle their proteins as a form of necessary housekeeping – but it comes at a cost. The energy consumed in this process can generate molecules called reactive oxygen species, or ROS, which cause random damage in the cell. “This is damage happening in the background all the time,” says Elvan Böke at Center for Genomic Regulation in Spain. “The more ROS there is, the more damage there’s going to be.”

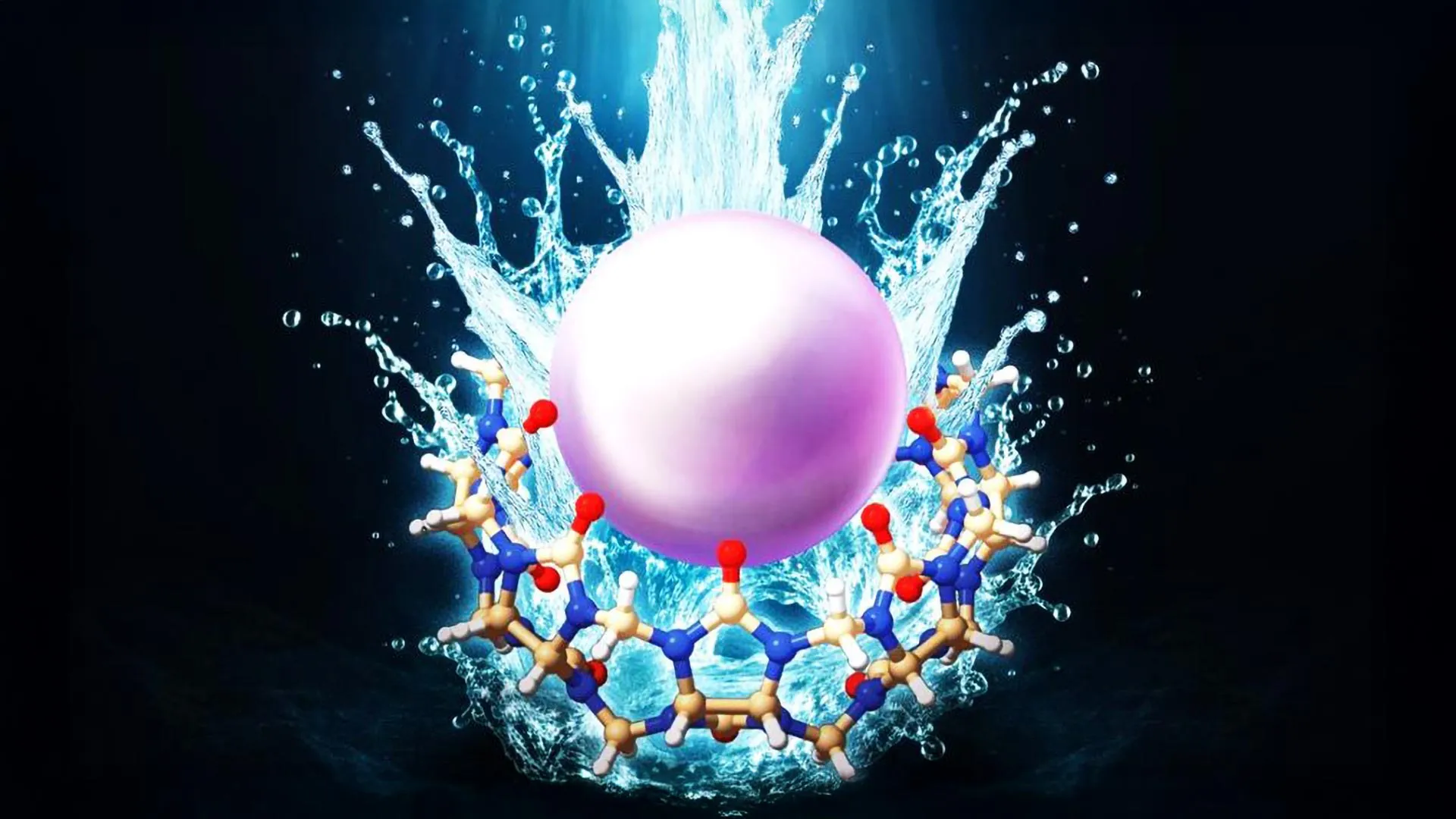

But healthy eggs seem to avoid this issue. To find out why, Böke and her colleagues studied harvested human eggs under a microscope. The cells were placed in a liquid with fluorescent dyes, which bind to acidic cellular components, called lysosomes, that behave as “recycling plants”, says Gabriele Zaffagnini at the University of Cologne in Germany.

The bright dye revealed the waste-disposing lysosomes in human eggs were less active than the same components in other human cell types or those in the egg cells of smaller mammals, like mice. Zaffagnini and his colleagues say this may be a form of self preservation.

Slowing down their waste-disposal mechanism may be just one of many ways human egg cells achieve their relatively long lifespans, says Zaffagnini. Böke speculates to avoid damage, the human oocytes “put a brake on everything”. If all cell processes run slower in human egg cells, she says, this could result in lower levels of harmful ROS, and therefore less risk of damage.

Since delaying the protein-recycling process seems to help egg cells maintain their health, failing to do so could explain what makes some oocytes unhealthy. “The way I see this is, it could be a clue into why human oocytes really become dysfunctional after a certain time,” says Emre Seli at Yale School of Medicine. “It could be a segue into advanced assessment of all the things that go wrong in human oocytes,” he says.

Fluorescent dye lights up a human egg cell, revealing components like mitochondria (orange) and DNA (light blue)

Gabriele Zaffagnini/Centro de Regulación Genómica

Assessing egg health in this way could eventually improve fertility treatments. “We do know that protein degradation is essential for cell survival, so it 100 per cent does affect fertility,” says Böke. She notes the study focused on healthy eggs; she says work to compare those cells with eggs from people affected by complications with fertility is ongoing. “If there’s high ROS in the cell, there are poor IVF outcomes,” she says.

Human egg cells are still not well understood, because they are difficult to study. “[They are] hard to work with, because the sample limitation is an issue,” says Böke. Seli says this obstacle is one of “multiple layers” to the problem, which also include regulations restricting the study of egg cells and a lack of funding.

If these hurdles can be surpassed, Zaffagnini says, there may be “really surprising” results. “It’s really worth it,” he says.

Topics: