BBC

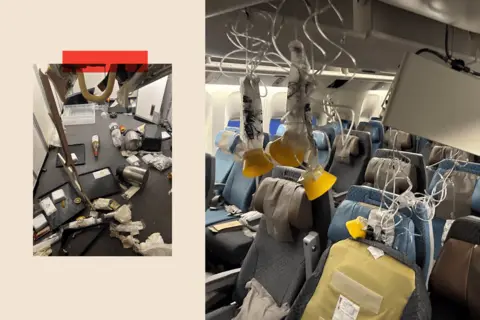

BBCAndrew Davies was on his way to New Zealand to work on a Doctor Who exhibition, for which he was project manager. The first leg of his flight from London to Singapore was fairly smooth. Then suddenly the plane hit severe turbulence.

“Being on a rollercoaster is the only way I can describe it,” he recalls. “After being pushed into my seat really hard, we suddenly dropped. My iPad hit me in the head, coffee went all over me. There was devastation in the cabin with people and debris everywhere.

“People were crying and [there was] just disbelief about what had happened.”

Mr Davies was, he says, “one of the lucky ones”.

Other passengers were left with gashes and broken bones. Geoff Kitchen, who was 73, died of a heart attack.

Death as a consequence of turbulence is extremely rare. There are no official figures but there are estimated to have been roughly four deaths since 1981. Injuries, however, tell a different story.

REUTERS/Stringer

REUTERS/StringerIn the US alone, there have been 207 severe injuries – where an individual has been admitted to hospital for more than 48 hours – since 2009, official figures from the National Transportation Safety Board show. (Of these, 166 were crew and may not have been seated.)

But as climate change shifts atmospheric conditions, experts warn that air travel could become bumpier: temperature changes and shifting wind patterns in the upper atmosphere are expected to increase the frequency and intensity of severe turbulence.

“We can expect a doubling or tripling in the amount of severe turbulence around the world in the next few decades,” says Professor Paul Williams, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Reading.

“For every 10 minutes of severe turbulence experienced now, that could increase to 20 or 30 minutes.”

So, if turbulence does get more intense, could it become more dangerous too – or are there clever ways that airlines can better “turbulence-proof” their planes?

The bumpy North Atlantic route

Severe turbulence is defined as when the up and down movements of a plane going through disturbed air exert more than 1.5g-force on your body – enough to lift you out of your seat if you weren’t wearing a seatbelt.

Estimates show that there are around 5,000 incidents of severe-or-greater turbulence every year, out of a total of more than 35 million flights that now take off globally.

Of the severe injuries caused to passengers flying throughout 2023 – almost 40% were caused by turbulence, according to the annual safety report by the International Civil Aviation Organization.

Brazil Photos/LightRocket via Getty Images

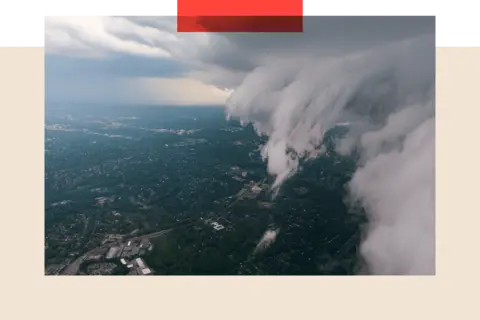

Brazil Photos/LightRocket via Getty ImagesThe route between the UK and the US, Canada and the Caribbean is among the areas known to have been affected. Over the past 40 years, since satellites began observing the atmosphere, there has been a 55% increase in severe turbulence over the North Atlantic.

But the frequency of turbulence is projected to increase in other areas too according to a recent study – among them, parts of East Asia, North Africa, North Pacific, North America and the Middle East.

The knock-on effect of climate change

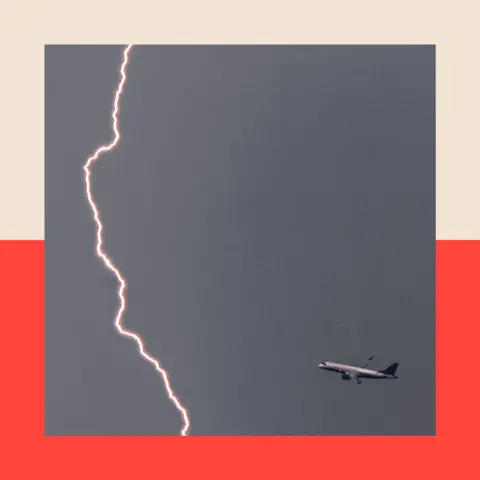

There are three main causes of turbulence: convective (clouds or thunderstorms), orographic (air flow around mountainous areas) and clear-air (changes in wind direction or speed).

Each type could bring severe turbulence. Convective and orographic are often more avoidable – it is the clear-air turbulence that, as the name might imply, cannot be seen. Sometimes it seemingly comes out of nowhere.

KIRILL KUDRYAVTSEV /AFP via Getty

KIRILL KUDRYAVTSEV /AFP via GettyClimate change is a major factor in driving up both convective and clear-air turbulence.

While the relationship between climate change and thunderstorms is complex, a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture – and that extra heat and moisture combine to make more intense thunderstorms.

Linking this back to turbulence — convective turbulence is created by the physical process of air rising and falling in the atmosphere, specifically within clouds. And you won’t find more violent up and downdrafts than in cumulonimbus, or thunderstorm clouds.

This was the cause of the severe turbulence on Andrew Davies’s journey back in 2024.

A report by Singapore’s Transport Safety Investigation Bureau found that the plane was “likely flying over an area of developing convective activity” over south Myanmar, leading to “19 seconds of extreme turbulence that included a drop of 178 feet in just under five seconds”.

MediaNews Group/Boston Herald via Getty Images

MediaNews Group/Boston Herald via Getty ImagesOne study from the US published in the Science journal in 2014 showed that for 1C increase in global temperature, lightning strikes increase by 12%.

Captain Nathan Davies, a commercial airline pilot, says: “I have noticed more large storm cells spreading 80 miles plus in diameter in the last few years, something you’d expect to be rare.”

But he adds: “The large cumulonimbus clouds are easy to spot visually unless embedded within other clouds, so we can go around them.”

Clear-air turbulence could also soon rise. It is caused by disturbed air in and around the jet stream, (a fast-moving wind at around six miles in the atmosphere, which is the same height as where planes cruise).

Wind speeds in the jet stream travelling from west to east across the Atlantic can vary from 160mph to 250mph.

There is colder air to the north and warmer air to the south: this temperature difference and change in winds is useful for airliners to use as a tailwind to save time and fuel. But it also creates the turbulent air.

“Climate change is warming the air to the south of the jet stream more than the air to the north so that temperature difference is being made stronger,” explains Prof Williams. “Which in turn is driving a stronger jet stream.”

‘It should worry us all’

The increase in severe turbulence – enough to lift you out of your seat – could potentially bring more incidents of injury, or possibly death in the most severe cases. And some passengers are concerned.

For Mr Davies, the prospect of more turbulence is worrying. “A lot. Not just for me, but my children too,” he explains.

“I’m pleased there hasn’t been an incident as severe as mine but I think it should worry us all”.

More than a fifth of UK adults say they are scared of flying, according to a recent YouGov survey, and worsening turbulence could make journeys even more of a nightmare for these people.

As Wendy Barker, a nervous flyer from Norfolk, told me: “More turbulence to me equals more chance of something going wrong and less chance of survival.”

Aircraft wings are, however, designed to fly through turbulent air. As Chris Keane, a former pilot and now ground-school instructor says, “you won’t believe how flexible a wing is. In a 747 passenger aircraft, under ‘destructive’ testing, the wings are bent upwards by some 25 degrees before they snap, which is really extreme and something that will never happen, even in the most severe turbulence.”

For airlines, however, there is a hidden concern: that is the economic costs of more turbulence.

The hidden cost of turbulence

AVTECH, a tech company that monitors climate and temperature changes – and works with the Met Office to help warn pilots of turbulence – suggests that the costs can range from £180,000 to £1.5 million per airline annually.

This includes the costs of having to check and maintain aircraft after severe turbulence, compensation costs if a flight has to be diverted or delayed, and costs associated with being in the wrong location.

Kevin Carter/GETTY

Kevin Carter/GETTYEurocontrol, a civil-military organisation that helps European aviation understand climate change risks, says that diverting around turbulence-producing storms can have a wider impact – for example, if lots of aircraft are having to change flight paths, airspace can get more crowded in certain areas.

“[This] increases workload for pilots and air traffic controllers considerably,” says a Eurocontrol spokesperson.

Having to fly around storms also means extra fuel and time.

In 2019 for example, Eurocontrol says bad weather “forced airlines to fly one million extra kilometres, producing 19,000 extra tonnes of CO2.”

With extreme weather predicted to increase, they expect flights will need to divert around bad weather such as storms and turbulence even more by 2050.

“Further driving up the costs to airlines, passengers and [increasing] their carbon footprint.”

How airlines are turbulence-proofing

Forecasting turbulence has got better in recent years and while it is not perfect, Prof Williams suggests we can correctly forecast about 75% of clear-air turbulence.

“Twenty years ago it was more like 60% so thanks to better research that figure is going up and up over time,” he says.

Aircraft have weather radar that will pick up storms ahead. As Capt Davies explains, “Before a flight, most airlines will produce a flight plan that details areas of turbulence likely throughout the route, based on computer modelling.”

It is not 100% accurate, but “it gives a very good idea combined with other aircraft and Air Traffic Control reports once we are en-route”.

RUNGROJ YONGRIT/EPA – EFE/REX/Shutterstock

RUNGROJ YONGRIT/EPA – EFE/REX/ShutterstockSouthwest Airlines in the US recently decided to end cabin service earlier, at 18,000ft instead of the previous 10,000ft. By having the crew and passengers seated with belts on ready for landing at this altitude, Southwest Airlines suggests it will cut turbulence-related injuries by 20%.

Also last year, Korean Airlines decided to stop serving noodles to its economy passengers as it had reported a doubling of turbulence since 2019, which raised the risk of passengers getting burned.

From owls to AI: extreme measures

Some studies have taken turbulence-proofing even further, and looked at alternative ways to build wings.

Veterinarians and engineers have studied how a barn owl flies so smoothly in gusty winds, and discovered wings act like a suspension and stabilise the head and torso when flying through disturbed air.

The study published in the Royal Society proceedings in 2020 concluded that “a suitably tuned, hinged-wing design could also be useful in small-scale aircraft…helping reject gusts and turbulence”.

Separately, a start-up in Austria called Turbulence Solutions claims to have created turbulence cancelling technology for light aircraft, where a sensor detects turbulent air and sends a signal to a flap on the wing which counteracts that turbulence.

These can reduce moderate turbulence by 80% in light aircraft, according to the company’s CEO.

NurPhoto via Getty

NurPhoto via GettyThen there are those arguing that AI could be a solution. Fourier Adaptive Learning and Control (FALCON) is a type of technology being researched at the California Institute of Technology that learns how turbulent air flows across a wing in real-time. It also anticipates the turbulence, giving commands to a flap on the wing which then adjusts to counteract it.

However Finlay Ashley, an aerospace engineer and member of Safe Landing, a community of aviation workers calling for a more sustainable future in aviation, explained that these types of technology are some time away.

“[They’re] unlikely to appear on large commercial aircraft within the next couple of decades.”

But even if turbulence does become more frequent, and more severe, experts argue this isn’t cause for worry. “It’s generally nothing more than annoying,” says Captain Davies.

But it might mean more time sitting down, with the seat-belt fastened.

Andrew Davies has already learnt this the hard way: “I do get a lot more nervous and don’t look forward to flying like I used to,” he admits. “But I won’t let it define me.

“The moment I sit down, my seat belt goes on and if I do need to get up, I pick my moment – then I’m quickly back in my seat, buckled up again.”

Top Image credit: Ivan-balvan via GETTY

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.