This is largely in line with the work of another psychologist, Robert Rescorla, whose work in the ’70s and ’80s influenced both Wasserman and Sutton. Rescorla encouraged people to think of association not as a “low-level mechanical process” but as “the learning that results from exposure to relations among events in the environment” and “a primary means by which the organism represents the structure of its world.”

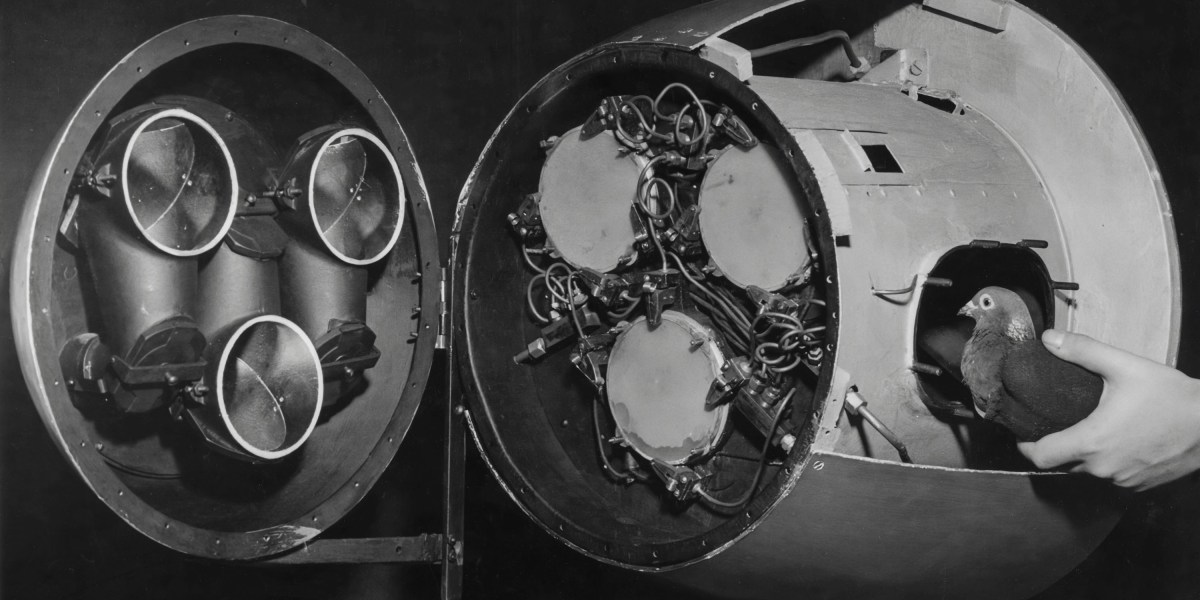

This is true even of a laboratory pigeon pecking at screens and buttons in a small experimental box, where scientists carefully control and measure stimuli and rewards. But the pigeon’s learning extends outside the box. Wasserman’s students transport the birds between the aviary and the laboratory in buckets—and experienced pigeons jump immediately into the buckets whenever the students open the doors. Much as Rescorla suggested, they are learning the structure of their world inside the laboratory and the relation of its parts, like the bucket and the box, even though they do not always know the specific task they will face inside.

Comparative psychologists and animal researchers have long grappled with a question that suddenly seems urgent because of AI: How do we attribute sentience to other living beings?

The same associative mechanisms through which the pigeon learns the structure of its world can open a window to the kind of inner life that Skinner and many earlier psychologists said did not exist. Pharmaceutical researchers have long used pigeons in drug-discrimination tasks, where they’re given, say, an amphetamine or a sedative and rewarded with a food pellet for correctly identifying which drug they took. The birds’ success suggests they both experience and discriminate between internal states. “Is that not tantamount to introspection?” Wasserman asked.

It is hard to imagine AI matching a pigeon on this specific task—a reminder that, though AI and animals share associative mechanisms, there is more to life than behavior and learning. A pigeon deserves ethical consideration as a living creature not because of how it learns but because of what it feels. A pigeon can experience pain and suffer, while an AI chatbot cannot—even if some large language models, trained on corpora that include descriptions of human suffering and sci-fi stories of sentient computers, can trick people into believing otherwise.

UNIVERSITY OF IOWA/WASSERMAN LAB

“The intensive public and private investments into AI research in recent years have resulted in the very technologies that are forcing us to confront the question of AI sentience today,” two philosophers of science wrote in Aeon in 2023. “To answer these current questions, we need a similar degree of investment into research on animal cognition and behavior.” Indeed, comparative psychologists and animal researchers have long grappled with questions that suddenly seem urgent because of AI: How do we attribute sentience to other living beings? How can we distinguish true sentience from a very convincing performance of sentience?

Such an undertaking would yield knowledge not only about technology and animals but also about ourselves. Most psychologists probably wouldn’t go as far as Sutton in arguing that reward is enough to explain most if not all human behavior, but no one would dispute that people often learn by association too. In fact, most of Wasserman’s undergraduate students eventually succeeded at his recent experiment with the striped discs, but only after they gave up searching for rules. They resorted, like the pigeons, to association and couldn’t easily explain afterwards what they’d learned. It was just that with enough practice, they started to get a feel for the categories.

It is another irony about associative learning: What has long been considered the most complex form of intelligence—a cognitive ability like rule-based learning—may make us human, but we also call on it for the easiest of tasks, like sorting objects by color or size. Meanwhile, some of the most refined demonstrations of human learning—like, say, a sommelier learning to taste the difference between grapes—are learned not through rules, but only through experience.

Learning through experience relies on ancient associative mechanisms that we share with pigeons and countless other creatures, from honeybees to fish. The laboratory pigeon is not only in our computers but in our brains—and the engine behind some of humankind’s most impressive feats.

Ben Crair is a science and travel writer based in Berlin.