Esme StallardClimate and science reporter, BBC News

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe government says it plans to pass legislation to permanently ban fracking for shale gas in England.

A moratorium on the practice was put in place by the last government but the debate has been reopened in recent weeks after the political party Reform committed to backing fracking if it came to power.

The Scottish and Welsh governments continue to remain opposed to the practise.

What is fracking?

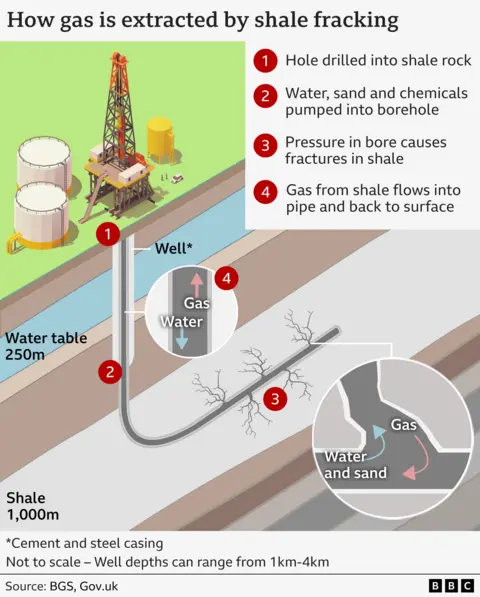

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a technique for recovering gas and oil from shale rock. It involves drilling into the earth and directing a high-pressure mixture of water, sand and chemicals at a rock layer, to release the gas inside.

Wells can be drilled vertically or horizontally in order to release the gas.

Why is fracking controversial?

The injection of fluid at high pressure into the rock can cause earth tremors – small movements in the earth’s surface.

In 2019, more than 120 tremors were recorded during drilling at a Cuadrilla site in Blackpool.

Seismic events of this scale are considered minor and are rarely felt by people, but they are a concern to local residents.

Shale gas is also a fossil fuel, and campaigners say allowing fracking could distract energy firms and governments from investing in renewable and green sources of energy.

Fracking also uses huge amounts of water, which must be transported to the site at significant environmental cost.

What has the government said about fracking?

Government policy on fracking has see-sawed over recent years. Former Prime Minister Liz Truss looked to reintroduce the practice, despite local opposition – but this was subsequently reversed by Rishi Sunak who introduced a moratorium.

In October 2025, at the Labour Party Conference, Energy Secretary Ed Miliband said the government would move to legislate against fracking, banning the practice permanently.

This follows a commitment made by the Labour Party in its manifesto and further commitments by PM Sir Keir Starmer in September that the practice would be “banned for good”.

But Reform has said it would seek to allow the practice should it be elected, as part of its “war” on renewable developers.

In his speech at the conference, Miliband said the practice was: “Dangerous and deeply harmful to our natural environment.

“The good news is that communities have fought back and won this fight before and will do so again,” he added.

Reuters

ReutersWhere has fracking taken place in the UK?

Fracking for shale gas in the UK has only previously taken place on a small scale, due to the many public and legal challenges.

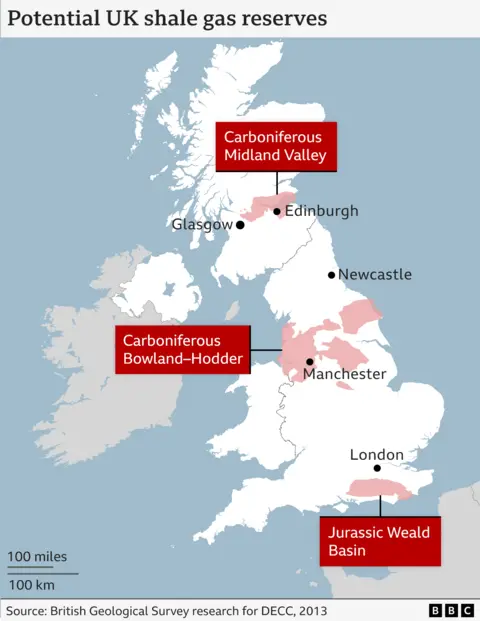

However, exploration has identified large swathes of shale gas across the UK, particularly in northern England.

More than 100 exploration and drilling licences were awarded to firms including Third Energy, IGas, Aurora Energy Resources and Ineos.

Cuadrilla was the only company given consent to begin fracking.

It drilled two wells at a site in Lancashire but faced repeated protests from local people and campaigners.

In 2022, the Oil and Gas Authority told Cuadrilla to permanently concrete and abandon the wells.

Could fracking lower energy bills?

The UK can only meet 48% of its gas demand from domestic supplies (this would be 54% if it did not export any gas).

Some MPs have claimed that restarting drilling at Cuadrilla’s two existing wells could be done quickly, and would provide significant supplies.

Cuadrilla claimed that “just 10%” of the gas from shale deposits in Lancashire and surrounding areas “could supply 50 years’ worth of current UK gas demand”.

Energy experts dispute this, pointing out that the UK’s shale gas reserves are held in complex layers of rock.

Mike Bradshaw, professor of global energy at Warwick University, says estimates of how much shale gas the UK has are not the same as the amount of gas that could be produced commercially.

But Prof Geoffrey Maitland, professor of Energy Engineering at Imperial College London, has said fracking could provide interim relief.

“Although shale gas will not provide an immediate solution to the energy security of the country, it could be used in the medium term to replace diminishing North Sea gas production and some gas imports,” he said.

Which other countries use fracking?

It is thought that fracking has given energy security to the US and Canada for the next 100 years, and has presented an opportunity to generate electricity at half the CO2 emissions of coal.

But the complex geology of the UK and the higher density of people makes extraction more challenging, according to experts.

Fracking remains banned in numerous EU countries, including Germany, France and Spain, as well as Australia.

Authorities in countries including Brazil and Argentina are split, with some banning the practice, and others allowing operations.