KFF estimates that 5.1 million Medicaid enrollees use home care, which provides medical and supportive services to help people with the activities of daily living (such as eating and bathing) and the instrumental activities of daily living (such as preparing meals and managing medications). Medicare generally does not cover home care (also known as home- and community-based services or HCBS), and Medicaid paid for two-thirds of home care spending in the United States in 2023.

In Medicaid home care, many people “self-direct” their services, giving them greater autonomy over the types of services provided and who they are provided by; and in some cases, allowing payments to family caregivers. Payments for caregiving can help mitigate the financial struggles family caregivers experience when they are forced to reduce their hours of work or quit their jobs on account of their caregiving duties. KFF focus groups of caregivers found that family caregivers often reported struggling to make ends meet and having to reduce the hours they are working other jobs due to the demands of caregiving. Self-directed services can also help address shortages of paid home care workers, which can be one of the factors placing additional strain on family caregivers. Beyond paying for their caregiving, Medicaid supports family caregivers with services such as training, support groups, and respite care (which is paid care that allows family caregivers to take a break from their normal responsibilities).

The 2025 reconciliation law, passed on July 4, includes significant changes to the Medicaid program that are estimated to reduce federal Medicaid spending by $911 billion over the next decade. Given the substantial share of Medicaid spending that pays for home care, and the optional nature of most home care programs, cuts to home care programs could occur as states respond to the reductions in federal spending.

Such changes could affect Medicaid supports to family caregivers, all of which are optional for states to provide. A reduction in the availability of those supports could exacerbate challenges for people who need home care and are unable to find other sources of care due to workforce shortages, which may be amplified by the Trump Administration’s intensified immigration enforcement and restrictive policies, since nearly one-in-three home care workers are immigrants. For family caregivers, many may need to continue to provide care without payments and other Medicaid changes could affect access to health coverage. According to AARP’s 2025 Caregiving in the US report, there are over 8 million family caregivers for whom Medicaid is their source of health insurance (13% of 63 million total family caregivers).

Amidst this background, this issue brief describes the availability of self-directed services and supports for family caregivers in Medicaid home care in 2025, before most provisions in the reconciliation law take effect. The data come from the 23rd KFF survey of officials administering Medicaid home care programs in all 50 states and the District of Columbia (hereafter referred to as a state), which states completed between April and July 2025. The survey was sent to each state official responsible for overseeing home care benefits (including home health, personal care, and waiver services for specific populations such as people with physical disabilities). All states except Florida responded to the 2025 survey, but response rates for certain questions were lower. Survey findings are reported by state and waiver target population, although states often offer multiple waivers for a given target population. Key findings include:

- All reporting states except Alaska allow Medicaid enrollees to self-direct their home care in at least some circumstances, and among those states, all allow enrollees to select, train, and dismiss their caregivers.

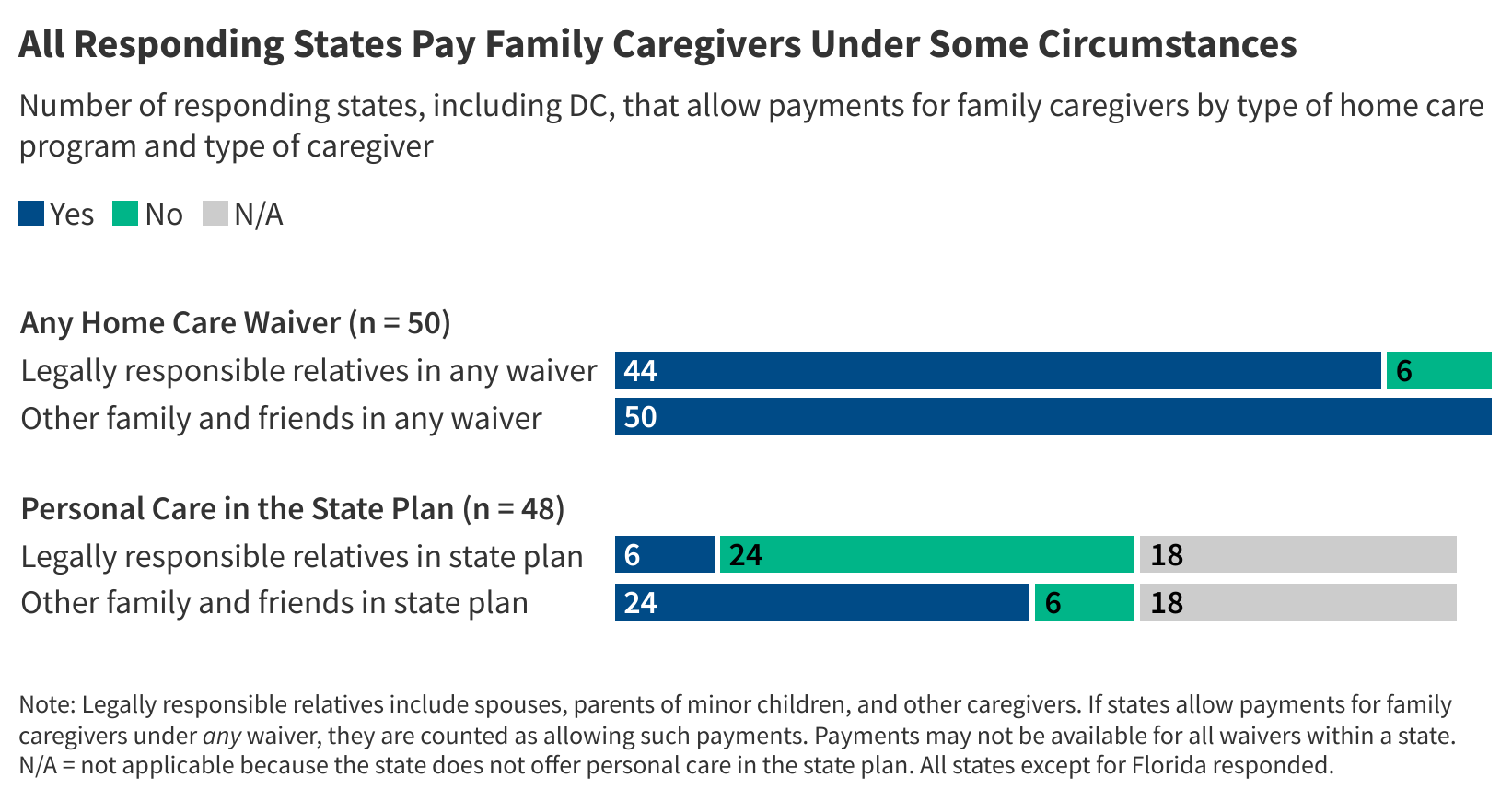

- All responding states pay family caregivers under some circumstances and provide family caregivers with other types of support, including respite care (Figure 1, Appendix Table 1)

- Family supports are most widely available for caregivers of people with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD).

How Many States Allow Medicaid Enrollees to Self-Direct Their Home Care?

Nearly all states allow Medicaid enrollees to self-direct their home care in some circumstances (Figure 2, Appendix Table 2). Self-direction came out of the “consumer-directed” movement for personal care services that started with demonstration programs in 19 states funded through grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Today, states may give people the option to self-direct home care through a wide variety of optional home care programs. States most frequently allow self-direction in waivers that serve people with intellectual or developmental disabilities, followed by people who are ages 65 and older or have physical disabilities. Among the 50 states responding to KFF’s survey, Alaska is the only state that reported not permitting self-direction under any of the home care programs.

Among states that authorize self-direction, all states allow enrollees to select, dismiss, and train workers (Figure 3). The ability to select, train, and dismiss workers is referred to as “employer authority” because it allows Medicaid enrollees (with the help of their designated representatives when appropriate) to decide who will be caring for them. All states with self-directed services programs provide employer authority to enrollees. Most states also allow enrollees to establish payment rates for their caregivers (41) and to determine how much Medicaid funding is spent among the various authorized services (39).

How Many States Pay Family Caregivers and Through Which Home Care Programs?

All responding states pay family caregivers through one or more Medicaid home care programs (Figure 1, Appendix Table 1). Family caregivers can generally be paid to provide personal care, which may be offered through several different types of Medicaid home care programs. Personal care may be provided through waivers such as the 1115 or 1915(c) programs, through the Medicaid state plan, or a combination of both. Waiver services tend to encompass a wider range of benefits than the state plan benefit, but waivers are usually restricted to specific groups of Medicaid enrollees based on geographic region, income, or type of disability; and are often only available to a limited number of people, resulting in waiting lists.

All responding states allow payments to family and friends through one or more waiver programs, but fewer states allow payments to legally responsible relatives. Forty-four states allow payments to legally responsible relatives through waiver programs. Payments to legally responsible relatives are less common than those to other family and friends because of additional legal requirements that pertain to payments to legally responsible relatives (Box 1). Payments to family caregivers are less common through the state plan—allowed by 24 states for other family and friends and by 6 states for legally responsible relatives. States pay family caregivers through the state plan less frequently because fewer states offer personal care through the state plan and because the legal requirements governing state plan services are more restrictive than those governing waiver services.

While all responding states allow payments to family caregivers, it is unknown what percentage of waiver participants are receiving paid care. KFF asked states, “What percentage of waiver recipients are receiving paid care from their legally responsible relatives/family members who are not legally responsible relatives?” Over two-thirds of states were unable to report the percentage of waiver recipients receiving paid care from either legally responsible relatives or other family members/friends. It is also unknown how often people with paid family caregivers also receive other paid care.

Box 1: What are the legal requirements for paying family caregivers?

Medicaid laws have more complicated requirements for states to pay legally responsible relatives than is the case for other types of family and friend caregivers. The specific legal requirements for paying family caregivers are complicated and differ across home care programs:

• For personal care offered through the state plan using section 1905 authority, there is a federal prohibition on paying for services provided by spouses and parents of minor children (which comprise most but not all legally responsible relatives). Other family and friends may be paid if they meet applicable provider qualifications, there are strict controls on the payments, and the provision of care is justified (which can be done when there is a lack of other qualified providers in the area).

• For home care offered through waiver programs, the requirements governing payments to family and friends are like those governing personal care through section 1905 authority. A key difference is that states may pay legally responsible relatives when the services being provided are “extraordinary care,” which is defined as care that exceeds the range of activities a legally responsible relative would ordinarily perform and is necessary to health, welfare, and avoiding institutionalization.

• For personal care offered through the state plan using one of the section 1915 authorities, states may pay legally responsible relatives using criteria like those of the waiver programs. However, some of those authorities designate a family member to be the recipient’s legal representative and may prohibit payments to legal representatives.

Payments for family caregivers are most common under waivers for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities (Figure 4, Appendix Table 3). Among the 47 states that responded to the survey and have waivers for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities, all 47 allow payments to family caregivers. There are fewer states with other types of waivers, and not all the other waivers allow payments to family caregivers. Among the 45 responding states with waivers for older adults and people with physical disabilities, 43 pay family caregivers, and among the 21 states with waivers for people with traumatic brain or spinal cord injuries, 19 do.

In most cases, family caregivers receive hourly wages like those of other employees, but 11 states have adopted programs known as structured family caregiving, in which family members are paid a per diem rate (Appendix Table 4). Structured family caregiving is a Medicaid benefit that supports unpaid caregivers of people who use Medicaid home care through waiver programs. In the structured program, Medicaid pays provider agencies a daily stipend for participants. The agency is responsible for directing a care coordinator or social worker and a nurse to oversee the family caregiver, answer health-related questions, and provide emotional support; conducting home visits about once per month; and passing a fixed percentage of the stipend (usually 50% – 65%) on to the family caregiver. Among the handful of payment rates reported in an overview of the program by the American Council on Aging, payments to family members are around $40 to $70 per day. States reported structured family caregiving programs in the following home care waivers:

- Older adults and people with disabilities in 9 states (Connecticut, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Rhode Island, and South Dakota),

- People with intellectual or developmental disabilities in 2 states (Indiana and New Hampshire),

- Medically fragile children in North Carolina,

- People with traumatic brain and/or spinal cord injuries in Indiana and

- People with Alzheimer’s and related disorders in Missouri.

Although KFF’s survey only includes home care waivers, according to the American Council on Aging, two states offered structured family caregiving as a standalone program: Massachusetts offers it as a state plan benefit through a program for adults in foster care, and Nevada has a standalone waiver to provide the benefit for caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s and related dementias.

What Other Types of Support Does Medicaid Home Care Provide for Family Caregivers?

All responding states provide support for family caregivers—who may be paid or unpaid—and most offer more than one type of support (Figure 5, Appendix Table 5). All responding states reported covering respite care, which provides short-term relief for caregivers, allowing them to rest, travel, attend appointments, or spend time with other family and friends. Other commonly covered benefits include caregiver training (37 states), and counseling or support groups (26 states).

Respite care may be provided anywhere from a few hours to several weeks at a time. Medicare only covers respite care for people who are receiving hospice care, which is only available for people who are terminally ill and electing to receive comfort care instead of curative care for their illness. That makes Medicaid’s respite care the primary source of coverage for caregivers of people with Medicare and Medicaid. Respite care is offered most frequently under waivers for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities (44 states) and older adults and people with disabilities (44 states).

Daily respite care is offered by the most states (43), followed by institutional respite care (40 states, Figure 6, Appendix Table 6). Daily respite care is available under waivers for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities in 34 states and available in 32 states within waivers for people who are ages 65 and older or have physical disabilities. Twenty-two states provide institutional respite care within waivers for people who are ages 65 and older or have physical disabilities and within waivers for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities. Weekly respite care is the least frequently offered (24 states total), and over half of states (32) report offering other types such as hourly, monthly, or annual.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.